(Article #1 of a series on the influence of Russian history on contemporary politics)

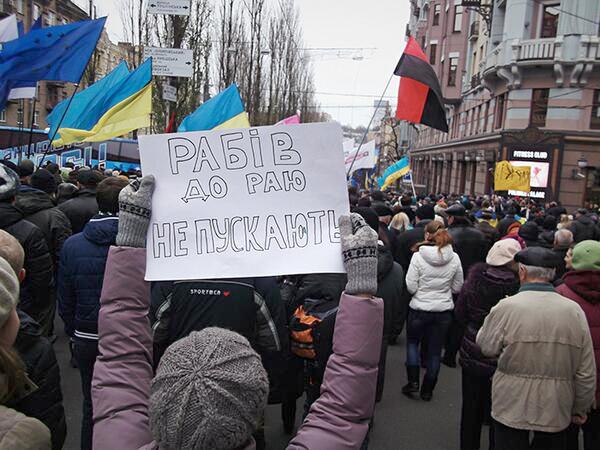

Demonstration in Kiev, Ukraine. The placard: “The entrance to Paradise is not permitted to slaves”.

This week a lot of Russian and Ukrainian websites reposted an article published by Zakhar Prilepin, one of the most popular Russian young writers in the official governmental Russian newspaper Izvestia. Prilepin is known as a leftist and a supporter of an extreme patriotic position, praising annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine.

Here are some quotes from his sensational new article:

“It is foolish to underestimate the Ukrainian people, or a substantial part of the Ukrainian people, for experiencing what is called ‘passionate explosion.’

“When we talk about the patriotic feelings of Russian people, about tens of thousands of Russian volunteers who are going to fight in Ukraine, about the humanitarian supplies which are sent over there by many, many Russians, we should be aware that in Ukraine the same thing is happening, but in a much, much more radical and ambitious forms.

“And the main reason for that is not the notorious tendency to share European civilization values, comfort and freedom. The main reason is a sharp and violent culmination of the struggle with the power that, as Ukrainians think, had always been oppressing Ukraine. This power is Russia, Russians.

“Ukrainians feel that now they not only passionately desire, but at last they can win the fight against the notorious ‘big brother’ but claim the title of ‘big brother’ for themselves. Then their ages-old dream will come true: they will be able to look down at this ugly, huge, formidable nation And, perhaps they even will be able to contribute to the disintegration of this despicable country, which had stolen from them a thousand years of glory, their statehood, their culture. For such an outcome, one can sacrifice a lot, even lives of many people.”

The original Prilepin’s article and its reposts in The Ukrainian and pro-Ukrainian Russian media have some differences. Prilepin makes it clear that he finds the Ukrainian dreams “delirious” and hopeless. In the re-posting this evaluation is skillfully replaced by the editors with expectation of the inevitable victory of Ukraine. In both cases the article made a real sensation.

In order to understand what Prilepin is talking about it is important to be aware of the impassioned discussions about Russian history that started in Russia after the fall of Communism and still keep going on.

So please permit me to provide some essential background information.

The Russian state first was created on the territory that included contemporary Russia, Ukraine and Belorussia with the center in Ukraine. It was Scandinavian Prince Rurik who first united and ruled over most of the East Slavic tribes, and his capital was settled in Kiev. The city is thought to have existed as early as 6th century, initially as a Slavic settlement. Gradually acquiring eminence as the center of the East Slavic civilization, Kiev reached its Golden Age as the capital of Kievan Rus’ in the 10th–12th centuries.

Rurik’s descendants ruled, fighting with each other in many East Slavic Cities and principalities for several generations.

Kiev was almost completely destroyed during the invasion of Tatar-Mongol Golden Horde in 12th-14th centuries.

The next principality that managed to conglomerate several East Slavic principalities in one state was Vladimir principality in 12th century.

Moscow was built by the Duke of Vladimir, Yuri Dolgoruky in 1147.

Later, the city gained independence and the Dukes of Moscow, skillfully using their close relationships with Tatar-Mongol rulers, gradually attached most of the East Russian principalities to their domain, first creating the extremely authoritarian and powerful Grand Duchy of Moscow, then becoming Czars of Russia, and finally creating the Russian Empire.

The territories of contemporary Belorussia and Ukraine, where Russian statehood’s history started, were not included into the new Russian State in part until the 17th and in part during the 18th centuries. Unlike the Moscow centered new Russia, influenced mostly by Tatar-Mongols, those territories were more influenced by European countries. Kievan Rus’ was the basis of Ukrainian identity.

Besides, unlike in West Russia, for many years Ukraine’s political structure was not a dictatorship, but a Cossack Republic. In 1638 the Republic joined Russia. Over time the Ukrainians started losing their freedoms step by step. The majority of Russians, all the peasants, were slaves, unlike the free Ukrainians. However, Catherine the Great turned Ukrainian peasants into slaves. Their territory received a new name: Ukraine, which means “Outskirt”, “Borderland”.

Both in Czarist Russia and in the Soviet Union, Historical textbooks of the history of Ukraine and Belorussia after 12th century was mostly neglected. Russia was presented as the only legitimate heir of all Russian cultural heritage, and Ukraine and Belorussia were treated as weak and inferior younger brothers.

(The real historical facts started to surface and be discussed in Russia only after Perestroika.)

At the beginning of 20th century there was even a period when a Ukrainian schoolteacher could be sent to prison for teaching Ukrainian language to his students. On the other hand, many talented Ukrainians preferred to move to Russia and willfully chose Russian language, as did Nikolai Gogol, who became one of the greatest Russian writers.

So the sentiments of Ukrainian nationalists can be understood. And there are people in Russia who sympathise with these sentiments.

Here is an opinion of a Russian blogger Dmitry Chernyshov:

”Hatred of a Russian ‘patriot’ for Ukraine is the hatred of a coward to a brave person. A coward, who could never stand up to bullets in the square, who will obediently tolerate lawlessness in his country and who will always seek to justify his cowardice: ‘What can I do? And where does a government not steal? It can become even worse. And we have already got used to our life’.

”Particularly disgusting is ‘the patriot’s’ obscene joy, which he experiences, when he sees any failure in Ukraine: ‘In place of the old thief, other thieves had come, so there was no need to punish the first thief. They did not want to go with Russia, they wanted to join Europe, but nothing had worked out, ha ha!’.

”My dear, the fact that not everything had turned out right in Ukraine from the first attempt, does not mean that all was in vain. Not at all. The reforms will happen and the fight against corruption will be victorious, and they will join Europe. All that will happen. And it should be welcomed by us. Ukraine is ahead of us. It makes mistakes, which we should not make in Russia. Because Russia finally will unite with Europe too. This is the only chance for our country’s development and preservation.”