Several years ago it was impossible to imagine, that somebody in Russia would officially and openly praise the GULAG of Stalin’s time.

But it is happening today.

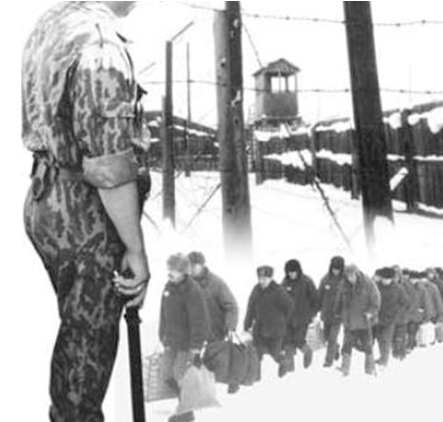

Last week in the northern Russian city of Solikamsk the workers of the Russian Penitentiary System celebrated the 75th anniversary of Usollag – one of the first camps of the GULAG.

Over the years Usollag held from 10 thousand to 30 thousand inmates. Prior to 1955, the camp imprisoned not only criminals, but also those convicted on “political” charges, ethnic Germans, wives of executed army officers and so forth. Among prisoners of Usollag there were such famous people as actors/directors Alexei Dikiy, who performed the role of Joseph Stalin himself on screen twice and Natalie Sats, the creator of theater for children.

In 1955, a couple of years after Stalin’s death, the remaining political prisoners were transferred from Usollag to other camps, and then Usollag became a camp for regular criminals.

The Camp’s Jubilee was celebrated lavishly.

Speakers fondly spoke of the importance of the camp and the benefits brought by it to the surrounding regions. They criticized modern values and the contemporary media that is creating negative image of such honorable institutions as concentration camps.

The event was attended by top officials of the region. They congratulated the staff of the penitentiary system of the region with the 75th Anniversary and gave them awards. After the meeting there was a concert.

At the meeting the representative of the regional council of veterans of Penitentiary Service of Russia Sergey Erofeyev said:

“The Usollag was created during hard times. It passed through many ordeals. It’s managers, it’s supervisors and civilian staff showed tremendous courage putting the institution on its feet and solving successfully industrial and social problems…

The NKVD established such traditions in Usollag in January 1938 that have great value in the present time.”

What are the traditions the speaker was talking about?

Here are some excerpts from memories of the inmates of Usollag:

“There were more then a hundred of us in the barrack. The best places on the wooden bunks where taken by thieves. To the right of the door a few bunks were occupied by syphilitics. There was only one water tank, and a common aluminum mug was chained to it. “

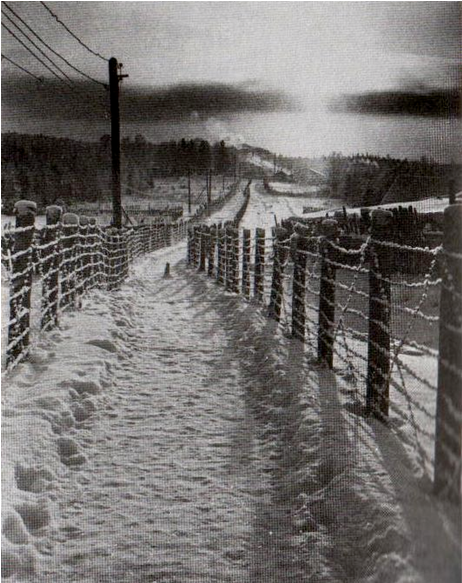

“It was a very cold winter (-40-49 F), we had no appropriate clothing. A prisoner should work cutting trees in the forest 12–16 hours a day to earn his bread ration (1.5 lb). People were dying; the corpses were taken away to the cemetery after the beep at 12:00 midnight. “

“I remember a case when 29 people died in one day in the barracks… When we were going to work, we were counted, and the same amount of people was expected to come back. Because of the scarcity of food, we had the disease – “chicken blindness”: people couldn’t see at night. Winter, cold … Go back, search for the missing men, until you find them. Many of them were found dead… Among inmates there were a lot of military wives and ethnic German women with little children, imprisoned without a trial. They, too, were forced to work. There was a nursery in the camp. When the baby turned 7 years old, it was taken from the camp and sent to an orphanage.”

Are those the traditions that need to be followed in Russia today?

It seems like an obscenity to celebrate a concentration camp, but it makes complete sense for people to feel gratitude for having jobs and to feel pride in performing them well. After a while, a concentration camp becomes simply a workplace, an enterprise that contributes to the local community by providing jobs.

How can a person take pride in an obscenity? Only by making it normal.

People are deeply grateful to have jobs. See how the construction workers support the Keystone XL pipeline even though it will harm the planet! Consider how proud the people of Fukushima were of their four nuclear reactors — before they melted down.

his is how we learn to learn to love what is obscene — to accept that which we should hate.

I found this searching for the exact name of one Lithuanian priest’s imprisonment place. He died there in 1950. Thank you for publication. Interesting previous comment for me as psychologist.