This year’s 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta demands Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court and legislature prohibit judges and courts from acting as prosecutors

by Bill Keisling

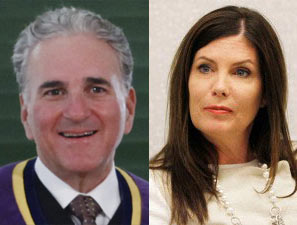

Any thoughtful person attending court proceedings against Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen Kane in the Montgomery County Courthouse this April 27 could not help but be offended, appalled and troubled by what he or she saw and heard.

• A judge acting with, and in concert to, a “special prosecutor” of the judge’s own appointment.

• Court papers and legal arguments were unavailable to any of the public who attended this supposedly “public hearing.”

• A grand jury presentment against Kane that was held secret for months.

• The same judge appointed two other judges to sit at this hearing, when it was not at all clear by what legal authority he had to appoint a three-judge panel of his own choosing, as again the paperwork was kept from the public.

• The highly inappropriate and unrelated sentencing of a wife beater to prison at the start of the Kane hearing because, well, that’s what the judge wanted to do.

It was all awful and offensive, and unbecoming a great, independent and fair judiciary, in a free country.

It was, in fact, by any measure, a kangaroo court that repeatedly and flagrantly violated Kathleen Kane’s fundamental right to due process in our commonwealth, and in our country.

What is this thing we call due process?

This year marks the 800th anniversary of the idea, enshrined into common law, and western conscience.

Our concept of due process stretches all the way back to the mists of western civilization and law, to June 15, 1215, when King John was forced to sign the Magna Carta.

Before the Magna Carta, a King and his Court were free to do pretty much whatever they pleased as, incredibly, we again saw last month in Judge William Carpenter’s courtroom in Montgomery County.

In Runnymede, an ancient Roman river crossing, in 1215, King John was made to sign a Great Charter, the 39th Clause of which reads:

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

This became the basis of the Fifth Amendment, called the Due Process Clause — one of the Bill Rights — enshrined in our American constitution, which reads in part:

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury … nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Since the Magna Carta, handed down through the centuries, the concept of due process, what it is, and what it isn’t, has rightfully taken its place in the western mind alongside such fundamental questions as, “What does it mean to be free?”; “What is free speech?” and, “What is freedom to worship?”

Over time these concepts have become so deeply rooted in us all — in the minds and actions of free people everywhere — that they defy codification in law, and are lessened by attempts to do so.

“It is now the settled doctrine of this Court that the Due Process Clause embodies a system of rights based on moral principles so deeply embedded in the traditions and feelings of our people as to be deemed fundamental to a civilized society as conceived by our whole history,” Justice Hugo Black wrote in the 1950 case Solesbee v. Balkcom. “Due Process is that which comports with the deepest notions of what is fair and right and just. The more fundamental the beliefs are the less likely they are to be explicitly stated.”

Simply put, like cruelty, or pornography, we know due process when we see it, and we also know when we don’t see it.

And fair due process was what we didn’t see in Montgomery County in the Kane case last month, with the judge acting, not independently, but in concert with his own appointed prosecutor.

In the 1934 case Snyder v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo wrote, “The commonwealth of Massachusetts is free to regulate the procedure of its courts in accordance with its own conception of policy and fairness, unless in so doing it offends some principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.”

As we saw in Montgomery County two weeks ago, a prosecutor working for and with a judge simply offends our sensibilities.

This offense to our “traditions and conscience” is precisely what we saw in the April 27 hearing against AG Kane.

How did we get here?

The month before, in March, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court gave its approval to Montgomery County Judge Carpenter appointing his own “special prosecutor,” Thomas Carluccio, in matters of breaches of grand jury secrecy or, it follows, internal court rules.

In an opinion dated March 31, state Supreme Court Justice Max Baer wrote, “When a court seeks to engage in fact-finding, it employs a special master, not a special prosecutor. The function of a special master is to gather necessary factual information, consider pertinent legal questions, and provide the court with recommendations. Special masters operate as an arm of the court, investigating facts on behalf of the court and communicating with it to keep it apprised of its findings; they do not act as independent prosecutors.”

By appointing Carluccio as a prosecutor, Baer cautions, Judge Carpenter went too far.

“In addition to penning an inappropriately broad order, Judge Carpenter also permitted improper and relatively constant ex parte (or private and one-sided) communication between Mr. Carluccio and himself, offending notions of fundamental fairness,” Baer writes. “While such communication may have been understandable if this scenario was simply one involving a special master, here, as noted, the court attempted to vest Mr. Carluccio with the vast general authority of a prosecutor. Additionally, even when it became apparent that the investigation had focused on the Attorney General, the supervising judge conducted ex parte hearings with the special prosecutor and selected witnesses, resulting in orders to the detriment of the Attorney General, all the while engaging the special prosecutor ex parte and excluding the Attorney General from both the court conferences and the ex parte hearings. Such insular ex parte hearings had none of the trappings of due process, and, were not confined to grand jury matters, but rather, resembled the actions of a district attorney in an adversarial, as opposed to investigative, role, which requires due process.

“…I believe that Judge Carpenter’s appointment order, which the (court’s opinion) seemingly endorses, attempted to bestow upon (Special Prosecutor) Carluccio power that far exceeded the authority to investigate contempt and to report his findings to the court,” Baer wrote.

In light of the appalling hearing two weeks ago, where an improperly empowered Judge Carpenter made a mockery of Kathleen Kane’s right to open and fair due process, Justice Baer’s concerns seem prescient.

No doubt many are comfortable in Montgomery County with Judge Carpenter’s unusual arrangement with his own “special prosecutor.” But safeguarding rights is seldom about comfort. Often safeguarding rights is about making powerful people uncomfortable.

The role of an independent judge, and judiciary, is instead rightly often to put a prosecutor in check, and to strike down a prosecutor’s actions when rights are violated.

That simply can’t happen when the judge is controlling and directing the prosecutor, as we see here.

That this should happen in Pennsylvania, our country’s cradle of freedom, where Abraham Lincoln traveled to speak of the government of the people, for the people, and by the people not perishing from the earth, makes it all the more appalling.

With the light of day now on its poor decision, the state Supreme Court should revisit this travesty of justice, history, and free society, and strike it down.

Sparing that, the state legislature should pass a law specifically barring a judge from appointing a special prosecutor.

This ancient form of tyranny, and lack of checks and balances, after all supposedly went out of fashion with King John and the Magna Carta, in the hallowed fields of Runnymede.

Let’s go a step further. Prohibit Lawyers from running for and becoming District Magistrates. Also prohibit judges from ever practicing law again after their term as judge ends.

Also put in place term limits on judges . It’s time to break up this sham legal system.