The following is a first draft of an excerpt from Bill Keisling’s forthcoming book on the history of corruption in Pennsylvania government. Over the past several decades, Keisling notes, as corruption in state government has grown worse, the state’s corporate media has often been complicit with the politicians. These media outlets, sadly, have been important supporting players in the state’s downward spiral.

Keisling writes, “The Larsen impeachment is particularly important to our book and readers, as it illustrates the growing problem with political sponsorship of bond underwriting in Pennsylvania, and how hard it is to attain a real investigation of this problem when every political figure is profiting from it. As well, we see how the state’s media, particularly the Philadelphia Inquirer, sided against giving readers the full story in order to destroy an enemy — a practice which they would embrace with increasing frequency in recent years.”

Keisling also writes: “Unfortunately for the public, special prosecutors Dennis and Tierney steadfastly refused the opportunity to conduct a comprehensive investigation into case fixing and corruption on the state Supreme Court, or to critically examine the closely related problem of no-bid public bond underwriting in Pennsylvania.”

One cannot understand state legislative actions that, for examples, made possible the Lancaster Convention Center and the current Lancaster CRIZ program, the bond debt that crippled Harrisburg, and yes even the persecution of former Attorney General Kathleen Kane, without familiarity with disreputable practices that have been going on over the decades and that caused Pennsylvania to be classified as one of the most corrupt states in the Union.

Rolf Larsen investigation of 1992 – ’93

On November 24, 1992, state Supreme Court Justice Rolf Larsen filed a 45-page Petition for Disqualification and Recusal of Justice Stephen A. Zappala and Justice Ralph J. Cappy, in which he “alleged that members of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and others, including attorneys and private citizens, had engaged in various forms of criminal and other misconduct,” as the memorable grand jury report would read.

Justices Zappala and Cappy had voted in October 1992 to discipline Justice Larsen with a minor reprimand — a slap on the wrist — for having an improper conversation in 1986 with a trial court judge.

Hoping to disqualify his high court brethren from the disciplinary vote, Larsen alleged that Justices Zappala and Cappy were “fix artists” with “a lust for power” who were conspiring to remove him, and other justices, from the court so they could take over.

Larsen painted Justice Zappala as little more than a conniving politician in a judge’s robe. He charged that Zappala had approached him in January 1992, and “told him that he, Justice Zappala, had been in contact with the Pennsylvania legislative leaders and that they (the legislative leaders) were unhappy with Chief Justice Nix serving as chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.” Legislative leaders were also unhappy with the prospect of Larsen as chief justice, he said Zappala intimated. This unhappiness with Larsen and Nix, he said Zappala told him, was “impacting adversely on the court’s budget and pay increases for the judiciary.” Zappala, Larsen wrote, suggested a solution to this “chief justice problem” by having the legislature initiate a “constitutional amendment making the position of chief justice an elected position as opposed to a seniority position as is presently the case.” This, Larsen wrote, would clear the way for Zappala to become chief justice, succeeded by Cappy, some eleven years Zappala’s junior.

“This overwhelming desire for the office of chief justice on the part of justice Zappala and justice Cappy was starkly evident at the sad occasion of the funeral of Justice McDermott in June of 1992,” wrote Larsen. He accused Cappy of coming up to him at the funeral and referring to Nix, who was “recovering from an illness and not feeling well.” Should Nix happen to die or resign, he wrote Cappy asked him, would Larsen waive his right to succeed Nix so that Zappala could become chief justice? Larsen, “knowing that Justice Flaherty has more seniority than Justice Zappala, responded by asking Justice Cappy: ‘What are you going to do with Justice Flaherty, who would be next in line to become chief justice?’ He says Justice Cappy responded, ‘Don’t worry, we (meaning Justice Cappy and Justice Zappala) will take care of him.” This “lust for power, control, and the office of chief justice,” argued Larsen, brought into question Zappala and Cappy’s impartiality as required by judicial canon.

Larsen went on to charge that Zappala illegally tape recorded telephone conversations. He passed along rumors that both Zappala and Cappy wear “bodywires” to surreptitiously record personal conversations.

As entertaining and perhaps enlightening as all this was, it was just back-room-court gossip compared to the heavy-duty charges Larsen dropped next. He accused Zappala of fixing cases. He wrote that Zappala should disqualify himself from matters involving Larsen because Zappala was being investigated by the Judicial Inquiry and Review Board and “by the federal government and federal law enforcement officials, to-wit:

“Justice Zappala is alleged to have arranged for one of his brothers to receive bonding work from various local governments in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and through multiple ‘layered corporations’ Justice Zappala is alleged to have received indirect ‘’kickbacks.'”

Larsen alleged that “Zappala’s clandestine interest in the ‘layered corporations’ has led to his gross misconduct in certain cases before this court involving three local governments which had purchased bonding services from justice Zappala’s brother — the city of Philadelphia, the county of Allegheny and the city of Pittsburgh — and where the temporary financial health of these municipalities was at risk.”

Zappala, Larsen alleged, at various times had met ex parte with representatives of these government bodies, and advised them the “‘route’ and procedures to use in prosecuting” their cases in “this court.” When these suits were filed “in the ipner in which Justice Zappala had counseled and directed, Justice Zappala then took charge and ‘guided’ (these suits) through the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in a ‘special’ manner.”

These various cases, involving labor difficulties with the cities of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, and Allegheny County, were subsequently resolved in favor of the governmental bodies, Larsen wrote, and against labor, “with the result that (the governmental bodies’) financial strength was maintained and thus the bonds that had been handled through Justice Zappala’s brother, to the indirect benefit of Justice Zappala, were rescued from risk and maintained their strength.”

Larsen wrote that he had dissented in these cases, exposing “flaws in the majority’s reasoning,” despite lobbying from Zappala for a united court. “A unanimous opinion is always less suspect than a divided or split court,” Larsen illuminated. As a result of his dissent, Larsen complained, Zappala “harbors great ill will and retaliatory feelings.”

Larsen’s petition would turn out to be a grave threat against the cozy and ultimately corrupting bond underwriting scheme that state lawmakers had concocted for themselves with with was called the Noah’s Ark Deal (Act 61) of 1985, and carried forward with other bond deals on the state and municipal levels.

(Act 61 reads: “The [turnpike] commission may sell such bonds, notes or other obligations in such manner and for such price as it may determine to be for the best interest of the Commonwealth.”)

In the 1985 Noah’s Ark Deal Republicans and Democrats each were allowed, on a no-bid basis, to appoint a bond underwriter and bond solicitors to underwrite $4.6 billion in Pennsylvania Turnpike bonds. It was called the “Noah’s Ark Deal” because there would be two of everything — one for each political party.

As part of the deal, the Democrats selected the firm Russell, Rea & Zappala (aka RR&Z, or RRZ Public Markets) as their “senior manager” for bond underwriting. A principal of that firm was the brother of Democrat Justice Stephen Zappala.

Several turnpike bond issues were floated between the 1985 Noah’s Ark Deal and Larsen’s November 1992 poison pen recusal petition, each with more or less similar rules of engagement. In 1989 some $240 million in no-bid bonds were sold to finance various projects and refinance others. In August 1992, $570 million in bonds were sold, this time solely to refinance earlier bond issues. In all, according to the industry publication The Bond Buyer’s tally, RR&Z became senior manager for all four turnpike bond issues between 1988 and 1992, totaling about $1.4 billion.

Many if not most or all of these bonding firms also formed political action committees, or PACS, with altruistic-sounding names, to tender “contributions” to the politicians.

Russell, Rea & Zappala’s in-house PAC, for example, was called “the Committee for the Advancement of State and Local Government.” In the six and some odd years from January 1987 to early 1993, RR&Z’s PAC donated $545,805.07 to political candidates or committees, according to state records. The contributions traveled all over the political and geographic map.

In those six or seven years between 1987 to early 1993, RR&Z’s Committee for Advancement of State and Local Government contributed an average of $90,967.51 a year. The biggest single year for contributions was 1991, when $126,999 was dumped into political coffers (this was the year before the turnpike’s 1992 $570 million bond issue). The second biggest year was 1989, which saw $111,275 contributed. This was the same year the turnpike floated $240 million in bonds. Off years for big bond floats, such as ’87 and ’88, saw contributions of only $68,906 and $57,275, respectively. RR&Z’s PAC gave $77,995.30 to candidates in 1992, the year Larsen filed his petition against Justice Zappala.

Which politicians or groups were the biggest winners of these profits from the Russell, Rea & Zappala’s PAC? A selected list of contributions in the period leading to Larsen’s accusations would include:

Governor Bob Casey (Democrat) $47,000

Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell (Democrat) $23,500

Attorney General Ernie Preate (Republican) $19,200

State Senator William Lincoln (Democrat) $15,150

New Jersey Republican State Committee $14,200

PA Senate Republican Campaign Committee $12,900

PA Democratic Senate Campaign Committee $11,675

State Treasurer Catherine Baker Knoll (Democrat) $12,000

State Senator Vincent Fumo (Democrat) $10,200

State Senator Robert Jubelirer (Republican) $ 7,200

PA Democratic State Committee $ 4,500

PA House Democratic Campaign Committee $ 4,400

Auditor General Barbara Hafer (Republican) $ 3,750

PA Republican State Committee $ 3,000

State Senator Robert Mellow (Democrat) $ 2,900

Judge Ralph Cappy $ 2,500

Lt. governor Mark Singel (Democrat) $ 2,300

State Rep. William DeWeese (Democrat) $ 1,500

PA House Republican Campaign Committee $ 600

Contributions were tendered to Philadelphia and Pittsburgh mayors Wilson Goode and Richard Caliguiri, when they were in office. A couple thousand dollars went to the Allegheny County Democratic caucus. Donations even began flowing out of state, demonstrating RR&Z’s growing strength and desire to compete nationwide. Many contributions went to candidates and committees in New Jersey, some to West Virginia, and some to Alabama, including a $1,000 donation to George Wallace, Jr., in 1988.

So the selection of these politically blessed bond firms opened great spigots (plural) of campaign contributions from all these bond underwriters and lawyers to candidates of both political parties. It was really a new and corrupting form of political patronage, whereby professional bond and legal beneficiaries repaid their political benefactors, or patrons. It was called pinstripe patronage.

As well, the bond money and political contributions began to flow, as I say, not just on the state level, but also in municipalities, as Larsen wrote, in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, and smaller places, like Harrisburg and Lancaster.

Russell, Rea & Zappala, for example, in November 1985 underwrote a $215,000 bond issue for the city of Harrisburg, for a failed hydroelectric dam project, on behest of Harrisburg Mayor Steve Reed. Due to environmental concerns the dam was never built, but the bond proceeds were applied to other projects, and also greased many professional palms. From this inauspicious beginning, Mayor Reed would throw caution into the wind and keep floating and remarketing bonds for decades, creating a patronage machine built on bond debt. By 2005 Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s capital city, would be insolvent under approximately $1 billion in bond debt.

Justice Larsen, at the heart of his 1992 recusal petition, complains that his fellow justice, Stephen Zappala, was unethically intervening in cases involving municipalities that to varying degrees were financed by his own brother’s bonds.

In particular, Larsen cited two cases in which Justice Zappala had curiously intervened on an emergency basis, using what were called the high court’s “King’s Bench” powers: 1992’s Port Authority case in Pittsburgh, and 1992’s PLRB case in Philadelphia.

Larsen’s allegations also rang true with observers at the Pennsylvania Turnpike, where Democratic state Sen. Vince Fumo was a patronage chief, and where Justice Zappala in 1989 had similarly intervened on a case called Wagman v. Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, involving a stalled construction project at a turnpike interchange financed by Russell, Rea and Zappala-sold bonds.

One thing was certain: Justice Larsen was right about the “ill will” the other justices on the high court harbored against him.

Larsen’s accusatory motion for Zappala and Cappy’s recusal went over as well as a zeppelin filled with concrete. Pennsylvanians were soon treated to the spectacle of various justices of their supreme court calling each other crooks, liars, strong-arm terrorists and/or crazy.

On December 6, 1992, Justice Cappy wrote to Chief Justice Robert Nix that Larsen had “made assertions against me in his Petition for Disqualification and Recusal which not only challenge my personal integrity, but also the integrity of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.” Cappy noted that the code of judicial conduct prohibited him “from making public comment on any matter which is presently in litigation before me.” He asked Nix to “appoint an independent ad hoc panel comprised of persons whose integrity is unquestionable” to investigate Larsen’s charges and report back to the public within sixty days. “As for me,” Cappy wrote, “I welcome enthusiastically the investiture of such a panel, less so for the inevitable complete demudding of my name than for the just response it will give to Pennsylvania citizens’ proper demand for accountability, fair play and truth-telling.”

Nine days later, on December 15, Larsen shot back by filing a supplemental petition for disqualification, in which he accused Cappy of violating Larsen’s right to due process by calling for the closed, ad hoc panel rather than an open hearing. He pointed out that Cappy’s self-described interest in “demudding” his own name displayed his bias against Larsen, “and thus, it is impossible for Justice Cappy to be an impartial and unbiased jurist in this matter to which (I am) entitled and which is required by the U.S. constitution and the Pennsylvania constitution.”

Larsen complained that Cappy’s letter amounted “to a pre-judged adjudication” of his case. He wrote that Zappala, on December 7, had “stated he was not joining Justice Cappy’s aforementioned letter” which called for the ad hoc panel. “Zappala specifically stated that he would handle (Larsen’s petition for disqualification) in his, Justice Zappala’s, own way — and that he, Justice Zappala had a ‘long memory.'”

Throwing even more caution to the wind, Justice Larsen then accused Justice Zappala and his friend and patronage beneficiary, state Sen. Vince Fumo, of attempting to run Larsen over with a car in front of the upscale Four Seasons Hotel in Philadelphia.

“Later that evening,” Larsen continued in his brief, “on Monday, December 7, 1992, (I) had alighted from an automobile which was stopped to the side of a private, covered driveway to a Philadelphia hotel. As (I) started to cross the said entrance driveway, a person standing in the near vicinity yelled with alarm to (me) to ‘watch out.’ Just (then) a vehicle commandeered by Justice Zappala and operated at an excessively high rate of speed drove perilously close to (my) person in an apparent attempt to run down and physically injure (me). Except for the warning to ‘watch out’ (I) would have been violently struck by the speeding automobile commandeered by Justice Zappala. This behavior of Justice Zappala makes it beyond dispute that (he) harbors malice, ill will, bias and prejudice toward (me).”

Larsen went on to complain that, the next day, Justice Zappala had read aloud and circulated a draft letter in which he described Larsen’s petitions as having caused a “‘tumultuous situation'” on the court. Zappala wrote “he would be refraining from making any public comment until the said ‘Larsen matter’ was disposed of; and further he, Justice Zappala, stated that he had been ‘advised’ that this ‘Larsen matter’ would be resolved in six to eight weeks,” Larsen reported. He complained again that he has been prejudged. Larsen asked, “Who has ‘advised’ Justice Zappala of this predetermined, arbitrary time frame?”

All this proved irresistible to state Attorney General Ernie Preate, who by mid-December 1992 announced he would appoint a special prosecutor to look into Larsen’s charges. It’s a measure of how low public trust had sunk in Pennsylvania that AG Preate was generally seen to have been running for governor by naming the prosecutor. But the truth was that Preate was, well, running for governor.

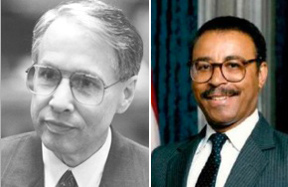

On December 12, 1992, AG Preate appointed two special prosecutors to supposedly examine Larsen’s accusations: former U.S. Assistant Attorney General of the Criminal Division Edward S. G. Dennis Jr., and James Tierney, former attorney general of Maine.

Ed Dennis was a former Ronald Reagan appointee to the U.S. Justice Department, and by 1992 was a private attorney and partner with the firm Morgan, Lewis, & Bockius.

Preate asked the legislature for $770,000 to pay for his special prosecutors’ investigation. This request found the AG in hearings with Sen. Fumo (who’d just been accused of trying to run Larsen down in a car), and now head of the Senate Appropriations Committee. Sen. Fumo asked why AG Preate needed $770,000 for this investigation, considering the AG’s already bloated $60 million budget. Fumo went so far as to question the attorney general’s authority to investigate the state supreme court.

The question of whether even the attorney general could investigate corruption in Pennsylvania courts was an interesting and telling one, rooted in the state constitution.

“The Pennsylvania Constitution eschews shared power in favor of extreme separation, conferring upon the judiciary almost exclusive control of court operations,” summarizes Prof. Charles Geyh in a 1995 essay about the Larsen impeachment partly titled The Limits of Judicial Self-Regulation. “Article V of the Pennsylvania Constitution so insulated judicial administration and rule-making from legislative scrutiny that nothing short of the constitutional crisis created by Justice Larsen’s impeachment prompted the Pennsylvania high court to implement reforms, the absence of which had made Justice Larsen’s misconduct possible. The appropriate solution is to amend the Pennsylvania Constitution to give the General Assembly some form of shared responsibility with the judiciary over judicial administration and rule-making, akin to that responsibility given Congress under the United States Constitution.”

In other words, in this and other matters in the coming years, state judges would say they alone had the power to investigate themselves. So much for accountability.

“Legal experts say the once-private dispute has turned into a public furor that could provoke a constitutional crisis, with questions of who should discipline the state’s judiciary,” reported The New York Times in a December 12, 1992 article. “Under Pennsylvania law, the Attorney General (Preate) says, the state has the power to investigate and prosecute accusations of criminal wrongdoing by any employee, including Supreme Court justices. But, so far, the Supreme Court has refused to cooperate while it is still considering Justice Larsen’s accusations.”

The seven-member state Supreme Court found itself all-but hamstrung.

House Speaker Bill DeWeese chimed in that $770,000 for a special prosecutor was ridiculous. “This is not the Manhattan Project,” he said. “We’re not inventing the atomic bomb.”

Maybe they were. At least, maybe they feared they were. DeWeese proceeded to make rumblings that he and other Democratic leaders would swiftly begin investigating the possibility of impeaching Larsen. Reporters asked if he was doing this to protect Justice Zappala, a charge which Rep. DeWeese said he “categorically” rejected. Luckily for Rep. DeWeese, the reporters didn’t ask, “Are you doing this to protect yourselves?”

Rep. DeWeese, as mentioned above, had himself drawn $1,500 from the wondrous Zappala bond money pump. Sen. Fumo had wet his lips to the tune of $10,200. AG Ernie Preate, had drunk in, over the years, $19,200, some of it in rather large chunks. Other legislators and their caucuses, like AG Preate, had also liberally wet their beaks with Zappala bond money.

(It perhaps should be noted here that AG Preate, Sen. Fumo, and Rep. DeWeese would all three, in time, be jailed for political corruption, unrelated to contributions from these bond underwriters.)

Not to worry about Appropriations Committee Chairman Sen. Fumo, the Philadelphia Inquirer assured its readers in late January 1993. This scandal wasn’t even out of the gate, and already the Inquirer was going into the tank against Larsen. The Inquirer, like the Pitsburgh Post-Gazette, had been sued for libel by Larsen since Larsen’s original 1983 disciplinary investigations. The libel lawsuits against the newspapers had dragged on for years, and were still pending in 1992, when Larsen filed his recusal petitions. The best way to win their libel case in court, the Inquirer’s managers reasoned, was to help destroy Larsen and see him impeached. They wouldn’t be held responsible for destroying the reputation of the first state judge to be impeached since 1811.

The Inquirer now reported that the AG’s office had some money in hand to pay the overpriced lawyers in the short run if Fumo’s appropriations committee wouldn’t pay, and perhaps the Republicans would force a floor vote to end-around Fumo.

The next day the Inquirer nailed another plank to the scaffold it’d been building. For months, between the lines, the Inky had been indirectly casting doubts about Larsen’s mental soundness. Now the Inquirer lifts a page from the script of Joseph Stalin. The newspaper begins to directly question Larsen’s mental stability. It allowed Vince Fumo, of all noble characters, to read the lines.

“State Sen. Vincent J. Fumo yesterday…said Larsen’s ‘mental stability’ should be examined in a House impeachment proceeding,” the Inky’s lead paragraph told readers on January 27, 1993. “‘If impeachment proceeds, it will probably be a hearing on the mental competence of Justice Larsen,’ said Fumo, a Philadelphia Democrat. ‘I’ve known Justice Larsen for a long time. This is just bizarre and unaccountable behavior. The whole thing is.'” Later in this article Fumo fesses up to being behind the the wheel of the car that Larsen wrote almost ran him over, but Sen. Fumo “disputed Larsen’s version, saying the car had not come within 20 feet of Larsen.”

The public would learn that Vince Fumo wasn’t simply in the car that Justice Larsen said had almost run him down. The chief of staff to Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell had arranged to loan an airplane to Senator Fumo to fly up to Erie to converse with Justice Zappala only a few days before the Rendell administration filed its emergency King’s Bench petition in the PLRB case — which was heard by Justice Zappala.

Larsen, upon learning of Fumo’s plane ride to see Justice Zappala on the eve of the PLRB King’s Bench petition, obviously calculated that he had Zappala and Fumo. In an honest government, with the involvement of honest investigators and prosecutors, perhaps he would have had him. Larsen didn’t count on Preate being a dishonest crook, he didn’t count on the state newspapers being in the tank, and he didn’t count on the involvement of Mr. Whitewash, Ed Dennis.

Larsen, for his part, at first refused to cooperate with AG Preate’s special prosecutors. Then came the orchestrated calls in the legislature to impeach him, though this was precisely the punishment the Judicial Inquiry and Review Board originally said would be the most unfair for Larsen’s transgressions. Suddenly the legislative judicial committees awakened from their decade-long comas to consider impeaching Larsen, who’d had the temerity to suggest Sen. Fumo’s pals were crooks. Legislative leaders from both parties were quick to say the judicial committees would only investigate Larsen. The committees would not look into allegations leveled against the whole court, and certainly not the legislature or its monetary donors.

Seeing the growing threat of impeachment, Larsen finally agreed to testify before a grand jury. Attorney General Preate, for his part, told reporters he wanted to wrap up his investigation “very, very quickly.” That’s a safe bet.

The report of the grand jury, issued in November 1993, relates, “Justice Larsen testified before the grand jury for a total of four days. During the last day, Justice Larsen was given an unrestricted opportunity to make his own presentation. Justice Larsen fully availed himself of that opportunity, making an unfettered statement which lasted several hours, during which he presented newspaper clippings, a book excerpt, and voluminous other materials for our consideration.”

Larsen told the grand jury, “I think you people will be fair. I do. Whatever the outcome, you just do justice, and I will be satisfied.”

But Justice, in the capital sense, was the last thing AG Ernie Preate had in mind. Preate would later be prosecuted and jailed (and by then Ed Dennis would be his personal defense attorney), partly on charges that he was adept at manipulating grand jury proceedings like this.

What Special Prosecutors Dennis, Tierney and AG Preate essentially would do was to ignore the spirit of what Larsen was saying, and focus on the gospel verse.

The first finding of their grand jury report, for example, reads, “There is no credible evidence to support Justice Larsen’s allegations that Justice Zappala was under federal investigation, or that he received kickbacks in exchange for obtaining municipal bonding business for his brother’s investment firm,” etc.

The problems and questions at hand really were more complicated, and nuanced, than that. For another example, as “senior manager,” or chief underwriter, of a bond deal, RR&Z made its profit selling turnpike or municipal bonds to other brokers when the deal was first cut, and wouldn’t necessarily be hurt should those government bodies run into financial problems years or even decades later, as in the case of Harrisburg’s insolvency.

What Larsen should have written, in hindsight, was that Justice Zappala was sitting on cases that unfairly benefited his friends and political allies, such as the turnpike’s Wagman case.

As for almost being run over by a car, the report states, for another example, “The evidence shows that Justice Zappala and Senator Fumo passed closely by Justice Larsen outside the Four Seasons on the evening of December 7, 1992, and that Senator Fumo drove at a rate of speed which may have been excessive for the entryway to the hotel. However, this encounter was the product of coincidence rather than design,” and so on.

On the one hand, while they took Larsen’s allegations quite literally, Preate and his team themselves gave themselves leave to dredge up new and totally unrelated matters.

Rather than get to the bottom of case fixing, bond underwriting, pinstripe patronage, and legislative or judicial corruption, AG Preate and his special prosecutors asked the grand jury to instead prosecute Larsen for obtaining anti-depression medications he’d illegally received through prescriptions written to his staff members.

As for fixing court cases for friends, Preate’s grand jury charged that Larsen had been doing the same for his own friends and associates — including suggesting he’d fix a case for Richard Gilardi, a lawyer who at the time was chairman of the state’s attorney disciplinary board, charged with prosecuting unethical lawyers.

Perhaps that’s why Larsen didn’t simply accuse his fellow justices of sitting on and fixing cases for friends or political patrons.

Justice Larsen himself was doing just that, as was perhaps every judge in the state.

Special prosecutor had bond conflicts of his own

Unfortunately for the public, special prosecutors Dennis and Tierney steadfastly refused the opportunity to conduct a comprehensive investigation into case fixing and corruption on the state Supreme Court, or to critically examine the closely related problem of no-bid public bond underwriting in Pennsylvania.

It would even turn out, perhaps predictably, that AG Preate’s chief investigator, Ed Dennis, suffered under his own outrageous conflicts-of-interest.

Conflict one: Ed Dennis had been billed as an “independent” prosecutor by Attorney General Preate, yet Dennis was involved in political fund raising for AG Preate. Conflict two: Ed Dennis, at the time he was empowered by Preate, had been defending a Philadelphia nursing home attendant who was under investigation by AG Preate; Ed Dennis had left the nursing home client he’d been defending from Preate to go to work for Preate in the Supreme Court investigation. Three: The law firm in which Ed Dennis was a senior partner, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, had signed on as co-bond counsel for a City of Philadelphia 1993 Water Department bond issue. Dennis now was a senior partner in a firm receiving large sums of money to opine that Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell’s administration was breaking no laws in the Larsen investigation. This at the same time Ed Dennis was supposedly investigating why Mayor Rendell’s office arranged a plane to fly Senator Fumo to see Justice Zappala.

The bond issue in question was an offering of $1.1 billion City of Philadelphia Water and Wastewater Revenue Bonds, Series 1993. The bond prospectus listed many of the parties Dennis was supposedly investigating, their names printed together in prospectus black ink. The Honorable Edward G. Rendell, Mayor. The offering, the prospectus reports, is subject to the legal opinion of Ed Dennis’s firm, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius. Listed among the many underwriters on the front page, we see “RRZ Public Markets, Inc,” the very firm accused by Justice Larsen of benefiting from decisions rendered by Justice Stephen Zappala, brother of the bond underwriter.