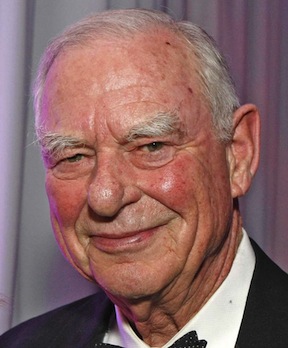

H.F. (Harold Fitzgerald) “Gerry” Lenfest, owner of the Philadelphia Inquirer, donated $10,000 to Pennsylvania House Speaker Mike Turzai’s campaign committee on October 4, 2014, in the same time frame as the Inquirer received the first of several rounds of state legal ads in late 2014.

In 2014 Lenfest also gave Gov. Tom Corbett’s campaign committee $2,000; and $2,000 to Republican State House Appropriations Chair Bill Adolph, and $1,000 to Democratic Senator Andy Dinniman.

Cozy relationships with state government brings newspapers millions

But are readers and taxpayers left in the dark?

Should distressed PA newspapers continue to have monopoly on state ad dollars?

(Editor’s note: This is Part 2 in a series. To read Part 1 click here. To view an Excel spreadsheet of the 2016 newspaper ads charged to the state as mentioned in this article click here. To view 2014 newspaper invoices for these ads in pdf format click here. To view the actual advertisement mentioned in this article click here.)

A state constitutional requirement intended to inform the public about government goings-on through newspaper advertising may be more helpful to state newspapers than the public.

It’s debatable whether the hundreds of newspaper ads purchased by state government before April’s primary election did much to inform the public.

What’s not debatable is that the windfall of taxpayer dollars spent on the newspaper ads certainly helped the newspapers, raises questions about political donations, and adds to a perception of a pay-to-play culture of corruption in Pennsylvania state government.

As I wrote last week, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has so far paid $2.6 million to state newspapers to advertise a proposed constitutional amendment to change the retirement age of judges from 70 to 75.

The proposed amendment went before voters this April 26.

Almost 2.4 million voters cast their ballots on the issue, and defeated the proposal by 47,594 votes.

But just days before the vote, heading into what looked like a losing election, judges and GOP legislators insisted the April vote not be counted, and ordered that a re-worded ballot question be placed before voters in the November general election — this time not informing the public that state judges currently must retire at 70.

If the judges get their way, not only will the 2,395,250 voters who cast their ballots in April’s election be disenfranchised.

The Wolf administration says it must spend another $1.3 million on newspaper ads before this fall’s general election to advertise the newly re-worded and deceptive ballot question.

Only in Pennsylvania, you might say.

What’s truly astonishing is the role the state’s newspapers and their owners are playing in this long-running charade.

So far voters and taxpayers have yet to be told much about this mess by the state’s newspapers, which themselves have received millions in public ad revenue from the growing scandal.

Rather than educate the public on this complicated constitutional issue, the state’s newspapers seem happy to quietly go along with the state’s political establishment.

But that’s putting it too mildly.

Rather than serving as independent watchdogs, Pennsylvania’s financially strapped newspapers, in line for another financial windfall of advertising from the state, seem to be in bed with the judges and the lawmakers.

This controversy, and these expensive newspaper advertisements, and how they are administered in Pennsylvania, all raise interesting questions in the Internet age.

Newspaper ad law, like Inquirer, rooted in 19th Century

The requirement that the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania advertise proposed constitutional amendments is rooted in the 19th century.

The purpose was, and remains, supposedly to inform voters.

The 1838 Pennsylvania constitution required that “the Secretary of the Commonwealth shall cause (any proposed constitutional amendment) to be published three months before the next election, in at least one newspaper in every county in which a newspaper shall be published.”

The state’s 1874 constitution changed this requirement to read that the ads must be published “in at least two newspapers in every county in which such newspapers shall be published.” This requirement remains in today’s state constitution.

“I’d wager most states have these newspaper legal advertisement laws,” says Gene Policinski, Senior Vice President of the First Amendment Center, and Chief Operating Officer of the Newseum, in Washington DC.

“And as you say, these legal advertisement laws are rooted in the 19th century,” Policinski tells me. “But these laws were intended and still are intended to reach the widest possible public audience. These kinds of requirements have to catch up to the Internet era, that’s true.

“But what’s important is to keep our eye on the goal of reaching and informing the largest number of people,” he says. “There’s still a sizeable number of Americans who don’t have Internet access. We have to keep the goal in mind of informing the public when we have very important constitutional amendments or legislation.

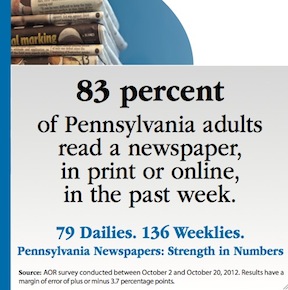

“When we look at newspapers in general, while circulation numbers aren’t what they used to, they still reach a significant portion of the public,” he says.

While in the future these laws may have to be changed to accomodate advertising on Internet publications, there’s another danger, Policinski says.

There’s been a push nationwide to eliminate ads in newspapers, he says, and “to only publish these notices in government publications.”

That would include dull digests like the Pennsylvania Bulletin, which is published by the state but is read mostly by government insiders, lawyers, and few members of the public.

How many states still require publication of ads in newspapers? It’s hard to say.

Ohio, for example, like Pennsylvania, specifically mentions newspaper ads in its constitution. “Such proposed amendments, the ballot language, the explanations, and the arguments, if any, shall be published once a week for three consecutive weeks preceding such election, in at least one newspaper of general circulation in each county of the state, where a newspaper is published,” reads Ohio’s constitution.

Delaware’s constitution as well requires that, “proposed amendment or amendments … be published three months before the next general election in at least three newspapers in each county in which such newspapers shall be published.”

Many states, like New York, make no specific mention of newspaper ads, but simply require that proposed constitutional changes “shall be published for three months previous to the time of making such choice.” So such notices, by statute, presumably can be placed in little-read government-published journals instead of privately held newspapers.

A web search reveals that many if not most states have also begun to post legal notices on websites.

But those legal notice websites, truth be told, are hard to read and search, and attract relatively few readers.

Legal ads don’t jump out at you on the web like they do from the pages of a newspaper. And that’s not even considering Internet technologies like web browser ad blockers, which prevent readers from seeing ads at all.

Selling eyeballs: Mansi meeting you here

As the Internet gains more readers, and print publications continue to wither, will newspapers like those in Pennsylvania lose their constitutional monopoly to publish paid legal advertisements?

“Your question is a valid one,” says Paul Boyle, head of government affairs operations for the Newspaper Association of America, in Washington DC.

“You want to put public notices where people see them,” Boyle tells me. “Newspapers still reach 100 million readers. What’s the most effective way of reaching the most readers in the broadest way possible? From our perspective newspapers deliver that.”

Boyle says that newspapers also often have “the top website in their local market, though you have this fragmentation going on.”

Newspapers, he says, can cross-publish government legal ads in both print pages and on their websites.

But should print newspapers in the Internet age continue to have a monopoly in the legal ad business in states like Pennsylvania? I asked. Some websites have greater readerships than many of the smaller state papers that publish state ads.

Boyle said he wasn’t familiar with Pennsylvania, and suggested I contact the state newspaper association for its opinion on how well the state’s system works.

But, in Pennsylvania, the state news media association isn’t complaining about the status quo, or the ad money from the state.

The Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association, which is the state newspaper and media association, itself owns the ad agency that places the newspaper ads for the state.

That’s right: the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association itself is the state vendor for these questionable newspaper advertisements.

The advertising arm of the PA NewsMedia Association is called Mansi Media.

“Formally known as Mid-Atlantic Newspaper Services, Inc., the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association created this affiliate (Mansi Media) in 1992 to help simplify the newspaper placement process for clients and advertising agencies,” Mansi’s website explains.

“Formally known as Mid-Atlantic Newspaper Services, Inc., the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association created this affiliate (Mansi Media) in 1992 to help simplify the newspaper placement process for clients and advertising agencies,” Mansi’s website explains.

Records provided by the state reveal that Mansi Media, since 2014, placed the $2.6 million in ads for the judges’ retirement ballot question.

And Mansi Media presumably is in line to place another $1.3 million in state ads for the fall ballot redux.

And the conflicts get more ridiculous.

Donations from Inky owner Lenfest

As I wrote last week, the Philadelphia Inquirer received the lion’s share of state ad money for the proposed judicial retirement constitutional amendment.

In 2014 and 2016, the Inquirer raked in $583,705.32 of the $2.6 million total, according to state records — or about 22 percent of the state’s entire ad budget. And the Inquirer stands to gain another juicy $300,000 from the fall ad campaign.

Stan Wischnowski, the executive editor of the Inquirer, the Daily News and philly.com, is listed as a member of the board of directors of the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association, which, through Mansi Media, places the lion’s share of the ads to, well, the Philadelphia Inquirer.

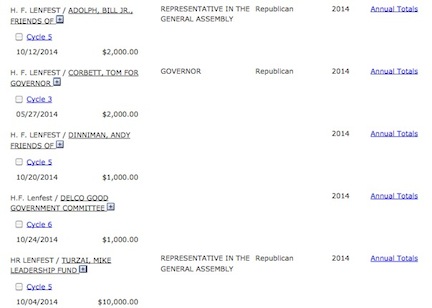

State campaign finance records moreover show that H.F. (Harold Fitzgerald) “Gerry” Lenfest, at the time the owner of the Philadelphia Inquirer, donated $10,000 to Pennsylvania House Speaker Mike Turzai’s campaign committee on October 4, 2014, in the same time frame as the Inquirer received the first round of state ads worth $291,852, in late 2014.

On October 12, 2014, Lenfest donated another $2,000 to Republican State House Appropriations Chair Bill Adolph.

Democratic Senator Andy Dinniman received a $1,000 donation from Lenfest on October 20, 2014.

Lenfest also gave Gov. Tom Corbett’s campaign committee $2,000 on May 27, 2014, state records show.

Lenfest’s generous donations didn’t stop there.

This January 2016, Lenfest donated his entire troubled Philadelphia newspaper company — the Inquirer, the Daily News, and philly.com — to a non-profit foundation.

So much for free enterprise.

PA NewsMedia Assoc and Mansi Media not forthcoming or cozy — with me

Armed with these and other questions, I telephoned Lisa Knight, Vice President of Advertising for Mansi Media.

I asked her about the $583,705 the Inquirer had received from Mansi for the ballot questions ads.

Knight said she didn’t know what I was talking about.

I told her I had two years’ worth of invoices and an Excel spreadsheet, given to me by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, with “Mansi Media” printed on the top, which relate that the Inquirer received $583,705.32 from the state for these ads, payable to Mansi Media.

“What Excel spreadsheet?” she said.

Knight said she didn’t know anything about the spreadsheet or invoices I was asking about, and requested that I email them to her so she could comment on them.

So I emailed Knight her own invoices. I’ve yet to hear back.

Next I called Teri Henning, president of the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association.

I asked Henning whether her association and Mansi might have a conflict in all this, and whether newspaper-type topics like transparency with public contracts are important.

What’s important, Henning says, is that these ads are “independent of government, and can be checked.”

Yes, I agreed, that’s important.

Henning gave me the association sales pitch.

Pennsylvania newspapers still reach 83 percent of Pennsylvania adults, she tells me.

She said the state NewsMedia Association also publishes public notices on its website, publicnoticepa.com, and has been doing so for twenty years.

I asked Henning how the public could be assured that the Philadelphia Inquirer wasn’t improperly compensated for running state ads.

“Our member newspapers have rate cards and rates,” she explains. And the Pennsylvania Newspaper Advertising Act of 1976 governs all this, she says.

Besides, she goes on, every newspaper in the association has a “firewall between editorial and advertising.”

Ah yes, the firewall. The Famous Philadelphia Newspaper Firewall. Some say that firewall went up in flames some time ago, like the MOVE building.

As I’ve previously written, in 1891 the Philadelphia Inquirer and other newspapers were caught bribing public officials in return for legal advertising.

For that matter there doesn’t seem to be much of a firewall on the state association’s board, where sits the Inquirer’s executive editor, Stan Wischnowski, who after all is passing along ad dollars through Mansi Media to his own newspaper.

Henning sounded angry with me. She said she’d be glad to talk with me in the future about policy matters important to the NewsMedia Association.

But this wasn’t one of those matters.

She hung up.

Inquirer: We know nothin’ about no stinkin’ Pennsylvania Newspaper Advertising Act of 1976

The Pennsylvania Newspaper Advertising Act of 1976, which supposedly governs legal advertising in Pennsylvania reads, in part:

§ 304: Establishment and change of advertising rates

“All newspapers of general circulation, official newspapers and legal newspapers accepting and publishing official and legal advertising, are hereby required to fix and establish rates and charges for official, legal and all other kinds of advertising, offered or accepted for publication, and such publications shall furnish, on demand, to any person having use for the same, detailed schedules, stating the rates and charges which shall be deemed to be in force and effect until changed or altered…”

So I called Mary Anne Logan, the Legal Advertising sales representative at the Inquirer. I asked for the Inquirer’s “detailed schedules” as described in the law, or a rate card for its legal advertising.

“Oh we don’t have that,” Logan tells me.

What about the $583,705.32 the Inquirer got from the state for the judicial retirement constitutional amendment ballot question? I asked her

“That was national advertising,” Logan tells me. “It came from an ad agency.”

You mean Mansi Media? I asked her. The arm of the state NewsMedia Association?

Yes, she said. Mansi placed the ad. But she didn’t have any rate information, she said. She asked me to send her an email with my questions.

The next day Logan wrote back to say, “The National legal rate for the Sunday Inquirer is $857 per inch; Daily Inquirer is $622 per inch; Daily News is $145 per inch; Daily combo rate for Inquirer/Daily News is $633 per inch.

“If you need anything else, please don’t hesitate to email/call me,” Logan wrote.

So I wrote back and asked her how many column inches were consumed by the state ads, and, again, whether the Inquirer had an advertising rate card.

Shortly thereafter Logan wrote back to say, “Please call my supervisor … in reference to your question.”

Then, an hour later, Logan sent me yet another email with the strange and cryptic message that she would “like to recall the message.”

The bottom line

There appears to be a too cozy of a relationship between the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association, its own advertising arm, Mansi Media, newspaper owners, and government officials.

How can all this coziness be changed? There’s plenty of irony in that question.

In Pennsylvania, the placement of these ads is enshrined in the state constitution.

To change the constitution, the legislature would have to vote to amend the constitution over two consecutive legislative sessions.

Then, per the constitution, and at the current cost of newspaper advertising, the state must buy $2.6 million in ads from the newspapers to advertise the proposed constitutional change…. You get the idea, and the problem.

Meanwhile, the hard question remains:

Who will tell the people?

This isn’t just a phenomenon in PA. I know New York and Florida have a similar law. I wouldn’t be surprised there is a variation in every state. These advertisements might be the only thing keeping some newspapers afloat.

I am extremely grateful for the continuing brave work of Bill Keisling. Thank you.

I am extremely grateful for the continuing brave work of Bill Keisling. Thank you.

Bill Keisling is only trying to drum up business for his online website by pissing on newspapers where Im guessing he couldnt get a job somewhere along the line, so he turned to blogging.

EDITOR:

Bill Keisling is author of more than a dozen books of fiction and nonfiction. His essays, investigative writings, and short stories have appeared in diverse magazines and journals including The North American Review, Rolling Stone, and The Progressive magazines. He was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship for his novel The Meltdown. The introduction to his first nonfiction book, Three Mile Island: Turning Point, was written by R. Buckminster Fuller.

Keisling grew up in close proximity to the Pennsylvania governor’s office, and the Pennsylvania Office of Attorney General. He has published several books on corruption in Pennsylvania government and the attorney general’s office, including The Sins of Our Fathers, We All Fall Down, and The Midnight Ride of Jonathan Luna.

He is also the writer and editor of Yardbird.com.