DRUG WAR CHRONICLE: The news last Sunday that acclaimed actor Phillip Seymour Hoffman had died of an apparent heroin overdose has turned a glaring media spotlight on the phenomenon, but heroin overdose deaths had been on the rise for several years before his premature demise. And while there has been much wailing and gnashing of teeth — and quick arrests of low-level dealers and users — too little has been said, either before or after his passing, about what could have been done to save him and what could be done to save others.

cooking heroin (wikimedia.org)

There are proven measures that can be taken to reduce overdose deaths — and to enable heroin addicts to live safe and normal lives, whether they cease using heroin or not. All of the above face social and political obstacles and have only been implemented unevenly, if at all. If there is any good to come of Hoffmann’s death it will be to the degree that it inspires broader discussion of what can be done to prevent the same thing happening to others in a similar position.

Hoffman, devoted family man and great actor that he was, died a criminal. And perhaps he died because his use of heroin was criminalized. Criminalized heroin — heroin under drug prohibition — is of uncertain provenance, of unknown strength and purity, adulterated with unknown substances. While we don’t know what was in the heroin that Hoffman injected, we do know that he maintained his addiction and went to meet his maker with black market dope. That’s what was found beside his lifeless body.

In a commentary published by The Guardian, actor Russell Brand, a recovered heroin addict, laid the blame for Hoffman’s demise on the drug laws. “Addiction is a mental illness around which there is a great deal of confusion, which is hugely exacerbated by the laws that criminalise drug addicts,” Brand wrote, calling prohibitionists’ methods “so gallingly ineffective that it is difficult not to deduce that they are deliberately creating the worst imaginable circumstances to maximise the harm caused by substance misuse.” As a result, “drug users, their families and society at large are all exposed to the worst conceivable version of this regrettably unavoidable problem.”

We didn’t always treat our addicts this way. Even after the passage of the Harrison Act in 1914, doctors continued for years to prescribe maintenance doses of opiates to addicts — and hundreds of them went to jail for it as the medical profession fought, and ultimately lost, a battle with the nascent drug prohibition bureaucracy over whether giving addicts their medicine was part of the legitimate practice of medicine.

The idea of treating heroin addicts as patients instead of criminals was largely vanquished in the United States, but it never went away — it lingers with methadone substitution, for example. But other countries have for decades been experimenting with providing maintenance doses of opioids to addicts, and to good result. It goes by various names — opiate substitution therapy, heroin-assisted theatment, heroin maintenance — and studies from Britain and other European countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, as well as the North American Opiate Medications Initiative (NAOMI) and the follow-up Study to Assess Long-Term Opiate Maintenance in Canada have touted its successes.

Those studies have found that providing pharmaceutical grade heroin to addicts in a clinical setting works. It reduces the likelihood of death or disease among clients, as well as allowing them to bring some stability and predictability to sometimes chaotic lives made even more chaotic by the demands of addiction under prohibition. Such treatment has also been found to have beneficial effects for society, with lowered criminality among participants and increased likelihood of their integration as productive members of society.

The dry, scientific language of the studies obscures the human realities around heroin addiction and opioid maintenance therapy. One NAOMI participant helps put a human face on it.

“I want to tell you what being a participant in this study did for me,” one participant told researchers. “Initially it meant ‘free heroin.’ But over time it became more, much more. NAOMI took much of the stress out of my life and allowed me to think more clearly about my life and future. It exposed me to new ideas, people (staff and clients) that in my street life (read: stressful existence) there was no time for.”

“After NAOMI, I was offered oral methadone, which I refused. After going quickly downhill, I ended up hopeless and homeless. I went into detox in April 2007, abstained from using for two months, then relapsed. In July 2008 I again went to detox and I am presently in a treatment center… I am definitely not “out of the woods” yet, but I feel I am on the right path. And this path started for me at the corner of Abbott and Hastings in Vancouver… Thank you and all who were involved in making NAOMI happen. Without NAOMI, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I am sure I would be in a much worse place.”

Arnold Trebach, one of the fathers of the drug reform in late 20th Century America, has been studying heroin since 1972, and is still at it. He examined the British system in the early 1970s, when doctors still prescribed heroin to thousands of addicts, and authored a book, The Heroin Solution, that compared and contrasted the US and UK approaches. Later this month, the octogenarian law professor will be appearing on a panel at the Vermont Law School to address what Gov. Peter Shumlin (D) has described as the heroin crisis there.

Phillip Seymour Hoffman (wikimedia.org)

“The death of Phillip Seymour Hoffman is a tragedy all the way around,” Trebach told the Chronicle. “It’s a bad idea to use heroin off the street, and he shouldn’t have been doing that.”

That said, Trebach continued, it didn’t have to be that way.

“If we had had a sensible system of dealing with this, he would have been in treatment under medical care,” he said. “If he was going to inject heroin, he should have been using pharmaceutically pure heroin in a medical setting where he could also have been exposed to efforts to straighten out his personal life, and he could have access to vitamins, weight control advice, and the whole spectrum of medical care. And if he had had access to opioid antagonists, he could still be alive,” he added.

While Hoffman may have made bad personal choices, Trebach said, we as a society have made policy choices seemingly designed to amplify the prospects for disaster.

“This is a sad thing. He is just another one of the many victims of our barbaric drug policy,” he said. “This was a totally unnecessary death at every level. He shouldn’t have been using, but we should have been taking care of him.”

The stuff ought to be legalized, Trebach said.

“I’m an advocate of full legalization, but if we can’t go that far, we need to at least provide social and psychological support for these people,” he said. “And even if we were to decriminalize or legalize, I would still want to figure out ways to provide support and love and kindness to people using the stuff. I advise you not to do it, but if you’re going to use it, I want to keep you alive. I remember talking to people from Liverpool [a famous heroin maintenance clinic covered in the ’90s by Sixty Minutes, linked above] about harm reduction around heroin use back in the 1970s. One of the ladies said it is very hard to rehabilitate a dead addict.”

“There are plenty of things we can be doing,” said Hilary McQuie, Western director for the Harm Reduction Network, reeling off a list of harm reduction interventions that are by now well-known but inadequately implemented.

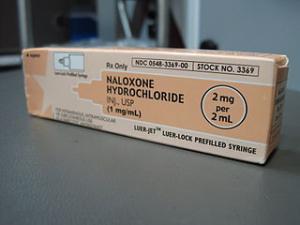

“We can make naloxone (Narcan) more available. We need better access to it. It should be offered to people like Hoffman when they are leaving treatment programs, especially if they’ve been using opiates, just as a safeguard,” she said. “Having treatment programs as well as harm reduction programs distribute it is important. We can cut the overdose rate in half with naloxone, but there will still be people using alone and people using multiple substances.”

There are other proven interventions that could be ramped up as well, McQuie said.

“Safe injection sites would be very helpful, so would more Good Samaritan overdose emergency laws, and more education, not to mention more access to methadone and buprenorphine and other opioid substitution therapies (OST),” she said, reeling off possible interventions.

Dr. Martin Schechter, director of the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, knows a thing or two about OST. The principal study investigator for the NAOMI and the follow-up SALOME study, Schechter has overseen research into the effectiveness of treating intractable addicts with pharmaceutical heroin, as well as methadone. The results have been promising.

“What we’re using is medically prescribed pharmaceutical diacetylmorphine, the active ingredient in heroin,” he explained. “It’s what you have when you strip away all the street additives. This is a stable, sterile medication from a pharmaceutical manufacturer. We know the precise dose tailored for each person. With street heroin, not only is it adulterated and injected in unsterile situations, but people really don’t know how strong it is. That’s probably what happened to Mr. Hoffman.”

Naloxone (Narcan) can reverse opiate overdoses (wikimedia.org)

In NAOMI, 90,000 injections were administered to study participants, and only 11 people suffered overdoses requiring medical attention.

“Never did we have a fatal overdose,” Schechter said. “Because it was in a clinic, nurses and doctors are right there. We administer Narcan (naloxone), and they wake up.”

Heroin maintenance had even proven more effective than methadone in numerous studies, Schechter said.

“There have been seven randomized control trials across Europe and in Canada that have shown for people who have already tried treatments like methadone, that medically prescribed heroin is more effective and cost effective treatment than simply trying methadone one more time.”

Those studies carry a lesson, he said.

“We have to start looking at heroin from a medicinal point of view and treat it like a medicine,” he argued. “The more we drive its use underground, the more overdoses we get. We need to expand treatment programs, not only with methadone, but with medically prescribed heroin for people who don’t respond to other treatments.”

Safe injection sites are also a worthwhile intervention, Schechter said, although he also noted their limitations.

“Injecting under supervision is much safer; if there is an overdose, there is prompt attention, and they provide sterile equipment, reducing the risk of HIV and Hep C,” he said. “But they are still injecting street heroin.”

He would favor decriminalizing heroin possession, too, he said.

Harm reduction measures, opioid maintenance treatments, and the like are absolutely necessary interventions, said McQuie, but there is a larger issue at hand, as well.

“We still need to look at the overall issue of the stigmatization of drug users,” she said. “People aren’t open about their use, and that puts them in a more dangerous situation. It’s really hard in a criminalized environment.”

Stigmatization means to mark or brand someone or something as disgraceful and subject to strong disapproval. Defining an activity, such as heroin possession, as a crime is stigmatization crystallized into the legal structures of society itself.

“The ultimate harm reduction solution,” McQuie argued, “is a regulated, decriminalized environment where it is available by prescription, so people know what they’re getting, they know how much to use, and it’s not cut with fentanyl or other deadly adulterants. People wouldn’t have to deal with all the collateral damage that comes from being defined as criminals as well as dealing with the consequences of their drug use. They could deal with their addictions without having to worry about losing their homes, their families, and their freedoms.”

While such approaches have a long way to go before winning wide popular acceptance, policymakers should at least be held to account for the consequences of their decision-making, McQuie said, suggesting that the turn to heroin in recent years was a foreseeable result of the crackdown on prescription opioid pain medication beginning in the middle of the last decade.

“They started shutting down all those ‘pill mills’ and people should have anticipated what would happen and been ready for it,” she said. “What we have seen is more and more people turning to injecting heroin, but nobody stopped to do an impact statement on what would be the likely result of restricting access to pain pills.”

The impact can be seen in the numbers on heroin use, addiction, and overdoses. While talk of a “heroin epidemic” is overblown rhetoric, the number of heroin users has increased dramatically in the past decade. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the number of past year users grew by about 50% between 2002 and 2011, from roughly 400,000 to more than 600,000. At the same time, the number of addicted users increased from just under 200,000 to about 370,000, a slightly lesser increase.

If there is any good news, it is that, according to the latest (2012) National Household Survey of Drug Use and Health, the number of new heroin users has remained fairly steady at around 150,000 each year for the past decade. That suggests, however, that more first-time users are graduating to occasional and sometimes, dependent user status.

And some of them are dying of heroin overdoses, although not near the number dying from overdoses from prescription opioids. Between 1999 and 2007, heroin deaths hovered just under 2,000, even as prescription drug deaths skyrocketed, from around 2,500 in 1999 to more than 12,000 just eight years later. But, according to the Centers for Disease Control, by 2010, the latest year for which data are available, heroin overdose deaths had surpassed 3,000, a 50% increase in just three years.

While the number of heroin overdose deaths is still but a fraction of those attributed to prescription opioid overdoses and the numbers since 2010 are spotty, the increase that showed up in 2010 shows no signs of having gone away. Phillip Seymour Hoffman may be the most prominent recent victim, but in the week since his death, another 50 or 60 people have probably followed him to the morgue due to heroin overdoses.

There are ways to reduce the heroin overdose death toll. It’s not a making of figuring out what they are. It’s a matter of finding the political and social will to implement them, and that requires leaving the drug war paradigm behind.