You would think someone in American government would care about Jonathan Luna.

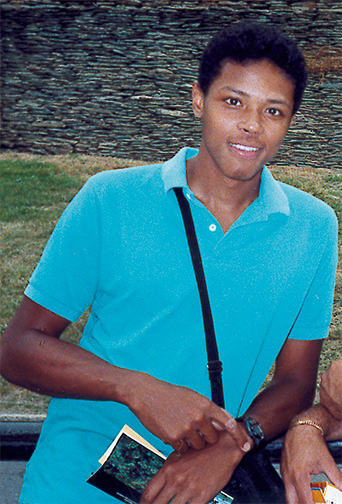

Luna was the young assistant U.S. Attorney who mysteriously vanished from his desk at the Baltimore federal courthouse shortly before midnight in December 2003. He was prosecuting a violent drug case when he disappeared.Luna’s body was found the next morning in an icy stream almost one hundred miles away, behind a deserted well-drilling company in rural Brecknock Township, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a few miles off the Pennsylvania turnpike.

Luna’s body had been stabbed dozens of times. His throat was slit, stab marks riddled his back and torso, and his hands were so badly sliced up and damaged by knife wounds that he had to be buried wearing gloves.

Luna’s death was quickly and for obvious reasons ruled a homicide by the Lancaster County coroner.

One would think that Luna’s superiors in the U.S. Justice Department, and the broader American government, would be interested in solving Luna’s murder, and would bring his violent killer or killers to justice. His being African-American added concern.

But as Luna himself learned in the last hours and days of his life, justice takes a strange backseat when the government has its own secrets to hide, and crimes of its own to conceal.

Consider the strange facts of Luna’s case:

Even while Luna lay dead in the stream, his superiors in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Baltimore violated the crime scene of Luna’s office, where he vanished.

They rifled through his desk and belongings and discovered his eyeglasses, which he needed to drive, his cell phone, and his laptop.

From his laptop they extracted an unfinished plea deal, which was ordered by Luna’s superiors, but which Luna himself didn’t want to complete, knowing it was unlawful.

His Justice Department superiors hurriedly and slapdashedly completed the plea agreement, signing it in his name, and rushed it down to a federal courtroom in the courthouse below, where a judge was presiding over Luna’s last catastrophic and compromised drug case.

Luna’s superiors did this, court records show, to prevent the federal judge from ordering an investigation into the FBI’s poor handling of Luna’s last case.

No one asked the federal judge to postpone the case until Luna’s whereabouts could be known.

Luna’s grisly and highly mysterious death remains classified a homicide in Pennsylvania.

Even so, almost from the day that Luna vanished, the FBI unofficially, through press leaks, strangely put out the word that Luna killed himself.

The FBI, unofficially, says that Luna left his office and amazingly drove without his eyeglasses hundreds of miles in the dead of night across Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, and halfway across Pennsylvania, stabbing himself in the back all the while as he drove, slicing up his own hands, slashing his own throat ear-to-ear, before throwing himself in an icy December stream in Lancaster County, where he drowned.

Sounds a little far-fetched, wouldn’t you say?

I ask Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter to help

In early 2005 I met with Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter to discuss Luna’s unsolved murder, and to ask for help. Specter, of course, at the time was an influential member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, with oversight of the FBI and federal courts.

Lancaster County businessman Ed Martino, of Honeybrook, arranged my meeting with Sen. Specter.

Martino had become interested in the case after reading a book I wrote on Jonathan Luna’s life and death, The Midnight Ride of Jonathan Luna. After he read my book, Martino had taken on an almost evangelical zeal to solve the case.For some years Martino had been a political volunteer for Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania, and suggested we seek the senator’s help.

Martino recently told me he arranged our meeting through one of Specter’s top aides, Tom Bowman, of Coudersport, Potter County. When Bowman died in 2009, he’d been working for Sen. Specter for 19 years.

“I knew Tom Bowman well,” Martino tells me. “I worked with Tom for years on political stuff for Arlen. He was Specter’s point man in Pennsylvania. If you wanted to get to Specter you had to go through Bowman.”

So one morning Martino and I drove down to Washington DC.

Specter had a spacious suite in the Senate Office Building. It was lined with political memorabilia, posters and photos going back to the Warren Commission in the early 1960s. Specter, after all, I was reminded, was the leading proponent of the single-bullet theory in the investigation into the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Martino and I spent some time talking with Specter’s chief of staff, David Brog. The senator himself, at first, was nowhere in sight.

Finally we left Specter’s suite to walk around the Senate Office Building. Suddenly here comes Arlen Specter through the throng, his head nearly bald from cancer treatments.

The senator greeted Martino warmly. He invited us to ride with him on the tram running from the office building to the capitol, where he said he had a hearing he must attend.

We get on the tram, and are about to embark, when a capitol policeman comes running up and asks what we’re doing.

“This tram is for senators only!” he barks at us.

He at first didn’t recognize Specter because of his balding head.

“I am a senator!” Specter grumbled.

Martino later told me that Specter was known for being querulous and demanding with staff members. “Arlen once put one of his young aides out of a car in Pennsylvania and told him he was out of a job,” Martino related.

Now, on the tram, at last recognizing the senator, the policeman began to apologize profusely.

“And do you know who these are?” Specter asks, pointing to Martino and me. “These are citizens!“

We start off on the tram, leaving the red-faced officer behind. On the way to the capital we exchanged pleasantries and small talk.

How was the senator’s health? I asked Specter. “I hear you’re back playing squash.”

“I am,” he says. “I’m taking chemotherapy and feeling much better, thank you.” Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma wouldn’t kill him for seven more years.

I handed Specter a copy of my Luna book and gave him a quick briefing. I asked that something be done to investigate Assistant United States Attorney Jonathan Luna’s death.

Specter listened to what I had to say. He examined the book I’d given him. “Why don’t you bring this out in a hardcover edition?” he asked.

I laughed and said I’d try to do that. I’m interested in trying to reach as many people as possible, I tell him, and a less-expensive paperback edition reaches more readers.

“Yes, of course,” he tells me.

We finally arrive at the capital. Sen. Specter bids us good day, thumps my book in his hand, and says he’s interested in reading it, and someone will get back to us.

We ride the tram back to the Senate Office Building where, on the platform, the embarrassed capital policeman who’d harangued us is still standing, red-faced and concerned.

“The senator’s not mad at me, is he?” the officer asks. “I honest-to-God didn’t recognize him!”

I tell the capital policeman everything is fine, and not to worry.

I left that day with the understanding that Arlen Specter would do something to get the ball rolling on a real investigation into the Luna case.

For years, until recently, I believed Specter had done something.

But this week Ed Martino told me that’s not what happened.