Pennsylvanians recently got a fleeting glimpse inside one of the most secretive, closely guarded, and problem-plagued programs run by the United States government.

I’m not talking about nuclear secrets, Area 51, or little green men kept in pickle jars in Hanger 18.

I’m talking about the confidential informant program administered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The program and methods used by the FBI to handle its informants, who are called “sources” in the trade, are among the holiest of holy secrets kept by the federal government.

Last month the U.S. Justice Department announced a plea deal with Pennsylvania political insider John Estey.

A few days later, Estey strolled into federal court to admit that he had stolen $13,000 from the FBI in a 2011 undercover sting of the Pennsylvania legislature.

All of this suggests that Estey — a former top aide to Gov. Ed Rendell and trusted confidant to many — as long as five years ago became a cooperating government informant with the FBI.

Reports surfaced that Estey may have been wearing a wire while he discussed legislation, government contracts, and political donations with elected Pennsylvania officials.

Needless to say, all this has left some of the highest-placed politicians in Pennsylvania government in a sweat, if not a paranoid lather.

But they shouldn’t panic!

Those officials, and the public, would do better to learn a thing or two about the FBI’s confidential informant program, and its nightmarish history.

Fact is, for more than half a century, the FBI has had severe problems with its Criminal Informant Program, as the operation is officially known.

These problems led to murders committed by FBI informants. FBI higher-ups, including most likely former director J. Edgar Hoover, not only knew that their informants were murdering people and breaking laws, but protected them.

These embarrassing revelations in turn led to congressional hearings and scathing committee reports.

Things got so out of hand that the U.S. Justice Department commissioned secret psychological studies of FBI agents to ascertain why they go bad working with informants.

FBI blunders with informants have also led to an unknown number of dropped cases and plea deals to conceal the problems.

In Pennsylvania, these problems led to the strange and violent death of a federal prosecutor from Baltimore, Jonathan Luna, who was found drowned and stabbed in a stream in Lancaster County.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Luna spent the last days and hours of his life unsuccessfully trying to conceal, in court, the misbehavior of an FBI informant who was caught dealing heroin and shooting up his inner city Baltimore neighborhood.

I wrote about Luna’s strange death and his last days battling the FBI’s ultra-secret confidential informant program in my book The Midnight Ride of Jonathan Luna.

Some of these same problems point to red flags that are relevant in the recent mysterious case of John Estey.

A bibliography of congressional and internal Justice Department reports of problems with the FBI’s confidential informant program, and the institutional failure of agents not following supposed guidelines, would include the following:

The Executive Summary of this 300-page report relates, “Our review found that FBI Headquarters has not adequately supported the FBI’s Criminal Informant Program, which has hindered FBI agents in complying with the Confidential Informant Guidelines. Although we noted some improvements in this area during the course of our review, in many instances agents lacked access to basic administrative resources and guidance that would have promoted compliance with the Confidential Informant Guidelines. For example, the FBI did not have a field guide or standardized and up-to-date forms and compliance checklists. The FBI also did not plan for, or provide, adequate training of agents, supervisors, and Confidential Informant Coordinators on informant policies and practices.”

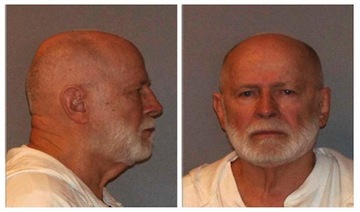

The report includes case studies of some of the FBI’s most notorious blunders, including FBI Agent John Connolly’s 2002 jail sentence for criminal misdeeds committed with two of his informants, Boston’s James “Whitey” Bulger, and Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi.

Both Bulger and Flemmi and other mobsters killed and committed crimes while working as FBI informants. And that’s not all — they were tipped off by FBI agents on whom to kill.

The Justice Department report states:

“Bulger, Flemmi, and other defendants were indicted in January 1995 and charged with multiple counts of racketeering, extortion, and other crimes. Four days after Flemmi’s arrest and the day before his indictment, the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) of the FBI’s Boston field office notified the U.S. Attorney in the District of Massachusetts for the first time that Bulger and Flemmi had been informants for the FBI for much of the period covered by the indictment. In August 1995, the government disclosed to the presiding magistrate that Flemmi had been a confidential informant for the FBI and that Flemmi’s informant file was being reviewed by senior DOJ officials to determine whether it contained any exculpatory material discoverable under Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963), and its progeny.

The Brady case, and similar cases, demand that prosecutors turn over to defendants all information that might help their cases with juries: such as deals or perks given to informants, and whether informants misbehaved while working under FBI supervision.

“In a 10-month evidentiary hearing that concluded in October 1998, after which the court denied Flemmi’s motion to dismiss the indictment, a federal judge heard evidence produced in response to Flemmi’s claim that the indictment against him should be dismissed based on ‘outrageous government misconduct,’ including a claim that the government promised that he and Bulger would be protected from prosecution as long as they continued to cooperate with the FBI about La Cosa Nostra. The judge heard evidence that (FBI Agent) Connolly and FBI Supervisory Special Agent John Morris became increasingly close to their informants and had filed false reports of information purportedly provided to them by the informants, ignored evidence that the informants were extorting others, caused the submission of false and misleading applications for electronic surveillance, and disclosed other confidential law enforcement information to them.”

FBI Agent Connolly “was tried and convicted in April 2002, the jury finding him guilty of multiple acts of obstruction of justice, including tipping Bulger to the 1995 indictment so he could flee.

“On May 4, 2005, (FBI Agent) Connolly was indicted in Florida for first-degree murder and conspiring with Bulger and Flemmi to kill John Callahan, a Florida businessman who was a financial adviser to the Winter Hill Gang. In addition, the Tulsa District Attorney’s Office charged another retired FBI agent, H. Paul Rico, who had been Flemmi’s original handler, with aiding and abetting murder. Rico died of natural causes at age 78 while awaiting trial.”

Released in 2003, this report summarizes House Committee Hearings on Government Reform relating to, as the title states, the FBI’s use of murderers as informants.

The Executive Summary of this congressional report relates:

“Federal law enforcement officials made a decision to use murderers as informants beginning in the 1960s. Known killers were protected from the consequences of their crimes and purposefully kept on the streets. This report discusses some of the disastrous consequences of the use of murderers as informants in New England.

“Beginning in the mid-1960s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation began a course of conduct in New England that must be considered one of the greatest failures in the history of federal law enforcement. This Committee report focuses on only a small segment of what happened.”

In the early 1960s, the report states, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover began recruiting mobster informants. His boss at the time was mob-busting U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

Soon, Boston FBI agent Paul Rico recruited Jimmy Flemmi and Joseph “The Animal” Barboza to work as FBI informants.

The 2003 congressional report suggests that the FBI agents and supervisors as high as J. Edgar Hoover knew the men were killers. FBI agents for example listened in on an unauthorized wiretap of Flemmi’s phone when he spoke with New England mob boss Raymond Patriarca. “An FBI agent who prepared a memorandum about the microphone surveillance noted that Flemmi and Barboza requested permission to kill Deegan,” the report notes. Deegan was shot dead a few days later.

The FBI had been so anxious to protect their informants that they allowed the murder of Deegan to proceed. The FBI likewise refused to bring Patriarca to trial for the murder. And this wasn’t an isolated instance:

“The Committee received testimony and other evidence that major homicide and criminal investigations in a number of states — including Massachusetts, Connecticut, Oklahoma, California, Nevada, Florida and Rhode Island — were frustrated or compromised by federal law enforcement officials intent on protecting informants,” the report reads. “It appears that federal law enforcement actively worked to prevent homicide cases from being resolved.”

How and why did all this come about?

Between the lines, the congressional report suggests that President Lyndon Johnson, fearful of his rival, Robert Kennedy, encouraged FBI Director Hoover to greatly broaden his contacts with the Boston mob.

LBJ apparently wanted Hoover to dig up skeletons in Bobby Kennedy’s own family closet.

It took two years for members of the U.S. Senate to learn that the FBI in 2000 completed its own internal study on agent misconduct. The FBI then stonewalled for months to keep its report from the Senate. Known as the Behavioral and Ethical Trends Analysis, or BETA, the report details a study conducted by the FBI’s Behavioral Sciences and Law Enforcement Ethics units. The FBI has since starved the Ethics Unit of funds.

The report focused on seventy-seven agents who had been caught, investigated and fired by the FBI from 1986 to 1999. The study helps to profile bad acting FBI agents. Bad actors aren’t newbies, the report finds. On average they’d been with the FBI for more than ten years before they were caught, and seventy percent had received bureau commendations. These, then, are agents who know the ropes. They’d also had a history of misconduct problems.

The bad actors working as FBI agents engaged in everything from child abuse, sexual fetishism to murder.

Senator Charles Grassley, an Iowa Republican who chaired the Senate Finance Committee, and Senator Patrick Leahy, a Democrat from Vermont on the Judiciary Committee, got wind of the BETA report in 2002.

Sens. Grassley and Leahy wrote the FBI for a copy of the BETA report. The senior senators didn’t receive the report until July 2003, shortly after former Massachusetts Senate President William Bulger was grilled by the House on his brother Whitey’s disappearance.

When the senators finally got the report, with it came a letter from the Justice Department stating the report contained “sensitive data” and “should not be publicly disclosed.”

On February 18, 2004 Grassley wrote FBI Director Robert Mueller about the report and the claims of secrecy surrounding it.

Grassley wrote Director Mueller that he had “concerns about the Behavioral and Ethical Trends Analysis (BETA) report, its alarming findings, a lack of response to the findings and recommendations, a general lack of support for the project and even efforts to prevent its completion, and attempts to withhold the report from Congress and the public.”

Grassley pointed out, “The BETA report almost never saw the light of day. Preliminary work began in 1996, but approval did not come until January of 1998. However, as the report states on page 80, ‘Funding was again delayed by FBI HQ in the fall of 1998.’ I understand there were other obstacles as well, but the report was finally completed in June 2000 and then presented to senior FBI officials. It was not released publicly, nor was its existence even announced.”

“The BETA report analyzed the worst of the worst at the FBI – agents whose actions were so egregious that they were fired and oftentimes prosecuted,” Grassley wrote. “Authored by the Behavioral Sciences Unit, with the aid of the Law Enforcement Ethics Unit, the shocking report is a laundry list of horrors, with examples of agents who committed rape, sexual crimes against children, other sexual deviance and misconduct, attempted murder of a spouse, and narcotics violations, among many others. For example:

- “A former agent had a severe gambling/alcohol problem and engaged in theft of informant funds to the excess of $400,000 resulting in an indictment, arrest, and imprisonment.”

- “This agent was dismissed for admission of unauthorized disclosures of classified information to individuals representing a foreign intelligence agency… SA (Special Agent) acknowledged disclosing a substantial amount of classified information about the FBI to others…”

- “Former agent pled guilty to manslaughter after killing his informant, after years of an inappropriate emotional and sexual relationship with her. He covered up the murder …”

- This agent was fired for criminal, sexual offenses involving numerous incidents of sexual behavior in public, including public masturbation and frequent assault on his victims.

Sen. Grassley writes that he was particularly concerned that the FBI had suppressed the report and cut funding to its authors.

“This is unfortunate because it sends a signal to the public, as well as to other law enforcement agencies in this country and around the world, that ethics is not important to the FBI,” Grassley wrote. “The specific role and mission of the ethics unit – to teach ethics to new agents and other agencies; and to cast a critical eye on the operations of the FBI and raise concerns about unethical practices – is now essentially gone, and the FBI is the worse for it. The ethics unit’s useful and important projects such as the BETA report, or the 1999 report on the double standard in discipline, will be no more.”

Director Mueller’s FBI responded predictably to Grassley’s release of the report. FBI Assistant Director Cassandra Chandler issued a press release describing the FBI’s BETA 2000 report as old and containing “anecdotal evidence.” But Mueller and Chandler knew that wasn’t true. If the report was old, it was only because the FBI sat on it for four years. And “anecdotal” is a lawyer’s phrase that seems misapplied to a scientific study involving almost eighty known wrongdoers.

Upshot: John Estey

We know from the gruesome murder and cover-up of federal prosecutor Jonathan Luna here in Pennsylvania that neither the U.S. Justice Department nor the FBI have done much to change their stripes.

The Justice Department will protect its informants at all costs, no matter what the informants may have done, or how complicit or incompetent their FBI supervisors.

Ultimately the FBI does this to shield its own incompetence from the eyes of the public.

What insights does all this shed on the recent and strange case of John Estey?

Red warning flags abound in Estey’s case. They all arouse suspicion:

Estey’s theft from an FBI sting unit. The long-running nature of his case. Estey’s close and presumably ongoing contacts to many in state government, including family members and law enforcement officials. Estey’s hidden plea deal. The failure, so far, to indict others.

It’s worth considering that Estey has yet to be named as a government witness in any prosecution brought in open court.

The related corruption case of former state Treasurer Rob McCord is also the subject of a shadowy federal plea deal. McCord received political donations from Estey.

As we saw in the Boston cases of Whitey Bulger and Stephen Flemmi, and the last Baltimore heroin case handled by Assistant U.S. Attorney Jonathan Luna, FBI malfeasance or incompetence only comes to light in open court, and not through secretive plea deals. Plea deals are a means to cover everything up.

We only learn the bad news after criminal defendants are told of an FBI informant’s behavior, or misbehavior, and lawyers for those defendants are allowed discovery, and to ask questions in open court.

Pennsylvanians should understand that the FBI is more interested in protecting its informant program than it is in protecting the public from corruption in the state legislature.