Pennsylvania has a political leadership problem, not just a school or tax problem

A Russian space satellite brought the greatest reform to Pennsylvania schools in the 20th century

Though many Pennsylvanians are unhappy with the rising cost of their property taxes and the declining quality of our public schools, they can probably forget about state lawmakers doing anything about it this year, or any time soon.

That’s because two week’s ago the state House Education Committee voted on a Republican-backed resolution to kick the can down the road by calling for yet another study on school district consolidation.

A Republican member of the Education Committee pointed out that there have been at least three similar studies undertaken in the last decade — and each study disagreed with the last, and they all came to naught.

A list of the contradictory studies reads like a roll call of truant students:

In June 2007, the joint Legislative Budget and Finance Committee, composed of senators and representatives from each party, commissioned a study by Standard & Poor’s (bottom line: the state might save $80 million dollars a year by consolidating school districts, but only if the right cost-cutting conditions are met. Critics said the study was unrealistic).

In December 2014, the Republican-controlled legislature’s Independent Fiscal Office released a report on what supposedly would happen if York County’s fifteen school districts were consolidated into a single, county-wide district with no accompanying tax reforms (bottom line: minimal savings, loss of state subsidies under current laws, and taxes could increase for most property owners.)

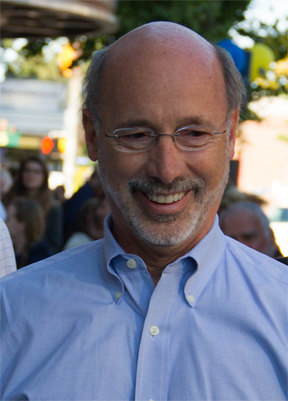

And just last year at this time, a House Democrat, Tim Mahoney, sponsored a resolution asking Gov. Tom Wolf to have the Department of Education conduct a study (bottom line: like the other studies, this proposal went nowhere).

This latest call for a study is just as doomed.

This year’s study to nowhere should be conducted by the State Government Commission and the Independent Fiscal Office, the Education Committee members decreed.

Rep. Kathy Rapp (R-Warren) incorrectly told the public that the issue of school consolidation is all about money.

“(At) the end of the day it is (about) a savings to the taxpayers,” Rep. Rapp says.

Why is she wrong?

As a national study in the Journal of Rural Education plainly states, “One thing is certain: arguments about district organization — be they about consolidation, home schooling, or charter schools within district — do not turn only on issues of money, as advocates on both sides are wont to maintain.”

It’s obvious that many citizens in Pennsylvania are hopping mad about rising real estate property taxes. There is moreover a widespread recognition that the state’s public schools and its students are in trouble. Public schools funding has been a crucial problem and stumbling block in state budget negotiations this entire decade. The issue contributed to Gov. Tom Corbett’s reelection loss. For the second year in a row, school funding is the main stumbling block in a budget deal, and may yet derail 2016’s budget talks. If left to worsen, the issue will likely threaten Gov. Wolf’s chances for reelection.

With an issue this important to so many, why can’t anything meaningful be done in Harrisburg?

The answer is that Pennsylvania has a political leadership problem, and not just a school or tax problem.

It’s not only that state politicians don’t seem to understand the issue. They don’t seem to understand how to even talk about the issue. So they keep asking for more studies.

How bad and intractable is this growing school and property tax problem?

To help confused and lost legislators, academics and citizens, there now are entire briefs, studies, and reading lists dedicated to the history of the problem and past attempts to fix it.

The best of these was published last year by Temple University’s Center on Regional Politics.

The Temple policy brief, titled “The Politics of Educational Change: What We Learn From the School Consolidation Acts of 1961 and 1963,” by J. Wesley Leckrone, a professor of political science at Widener, is must reading for anyone who wants to better understand the problem and work toward real solutions.

Prof. Leckrone makes clear the problem in Pennsylvania is not a school problem, or a tax problem, but, historically, a political problem.

Failed legislative efforts to voluntarily consolidate Pennsylvania schools actually began a hundred years ago — in 1901, and 1911.

Pennsylvania is a state of 2,561 municipalities, and state residents historically have preferred local control, and disliked centralized government.

For much of the twentieth century, just about each of those townships, boroughs and cities had their own school district, one-room school, and even high school.

Into the 1950s, the commonwealth had about 2,700 school districts.

Up to 1960, efforts to consolidate these school districts were voluntary. Only about 300 districts went away.

So, history tells us, the effort can’t be voluntary: few administrators are going to voluntarily eliminate their own jobs.

What happened to change all this?

In a word: Sputnik.

Leckrone writes:

“First, the post-World War II economy required skilled labor to accommodate new technology and increasingly complex social, political, and business organizations. This necessitated that schools teach a full range of college preparatory classes, particularly in science and math. Second, policymakers were concerned with the ability of the United States to match the technological advances of the Soviet Bloc. The launch of Sputnik in 1957 focused attention on the need to produce a new generation of better-educated citizens. Third, the educational infrastructure needed to meet these demands required larger, better-staffed schools. New services such as guidance counseling, health services and libraries, combined with the need to offer more varied instruction to advanced and remedial students, could only be accomplished with larger economies of scale. Finally, the costs of providing public education rose dramatically as a consequence of these reforms. Expenditures on education in Pennsylvania grew as an overall proportion of the state budget and showed no signs of abating. The pressure of accommodating more school-age Baby Boom children added to the need to stabilize spending.”

In other words, the public came to understand reforms were needed to keep up with our adversaries in the world.

Even so, in the 1960s, as today, there were hidden, unspoken issues standing in the way of school consolidation. Many feared racial integration. Many did not wish to assume the debt of neighboring school districts.

It took the leadership skills of two successive governors, Democrat David Lawrence and Republican Bill Scranton, to force reforms through the legislature. Lawrence in 1960 created a blue-ribbon Governor’s Committee on Education. The Republican-controlled legislature largely balked at the plan.

Scranton, when running for governor in 1962, initially opposed Lawrence’s school consolidation proposals. But upon his election as governor, Scranton changed course, tinkered with Lawrence’s plan to provide more local control, and pushed it through his party’s legislature in 1963.

With 500 school districts today, we’re actually running on the fumes of Lawrence and Scranton’s leadership skills — more than fifty years later.

“History suggests that strong gubernatorial leadership is needed to accomplish dramatic changes such as school consolidation,” writes Leckrone. “Governors Lawrence and Scranton are generally regarded as two of the most effective chief executives in the Commonwealth’s post-World War II era. (Gov. Ed) Rendell proposed further consolidation (in 2009), but his priority was enacting a school funding scheme based on ‘costing out’ the resources needed to provide every student with an ‘adequate’ education, whereas for Lawrence and Scranton, consolidation was a much higher priority.”

Simply stated, Gov. Rendell sold adequacy. Lawrence and Scranton sold excellence.

Voters and taxpayers must be convinced that it is in their best interest to change things for the better. It’s hard to convince people to make sacrifices or bet their property on an “adequate” outcome.

Where does Gov. Tom Wolf fit into this puzzle of politics and history?

Gov. Wolf summarized his approach to the problem in a single paragraph in his 2016 budget address:

“Pennsylvania is at a crossroads. We can fund our schools and fix our deficit or we will be faced with an additional $1 billion in cuts to education funding. Governor Wolf is fighting to restore the cuts made by the previous administration, but inaction by the Republican-controlled legislature has left us with underfunded schools and a ballooning deficit. If we build on a bipartisan budget agreement by increasing school funding we can take on the status quo and finally give our students the resources they need to succeed. If we fail to invest in our schools, we will see larger class sizes, teacher layoffs, and skyrocketing property taxes.”

All this only solidifies a public perception that Wolf merely wants to finger-point, and throw money at the problem.

But now isn’t the time to simply throw down money, or call for more studies.

To succeed, Gov. Wolf must articulate a serious plan with long-term vision, guide it with all the political skill he can muster, and back it with real political capital.

One thing we obviously don’t need is another study.

We need political backbone and a sound plan that must be sold to the public, and the legislature.

And only the governor can do that.

Nobody should lose their home because they are retired and can no longer afford the ridiculous budget increases these school boards pass every year.

Wolf still has Corbetts kick the can down the road what’s in it for me Crew.

Wolf signaled that he wasn’t serious about improving schools when he vetoed the bill that would have allowed schools to keep their best teachers in times of lay offs. Property taxes are bad, but we were supposed to get relief from the slots money, then it was the casino money, now you want to raise my income taxes. Pardon me if I’m skeptical, but you know the old saying. Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice shame on me.

You don’t want to pay a bit more in income taxes, fine. Who does. But how about you come up with a funding source that will fix the schools?

After what happened with all these casinos and we the people the state are getting nothing from them! We were told it would eliminate school and property taxes but in case no one noticed they keep going up instead! We were all lied to.

…older people on limited income are all in jeopardy every year of losing their home. If they can’t pay the school property tax, their home will be sold to pay the taxes. This great Governor we have now, said THAT is the sacrifice some must make for the cost of education.

Our kids are ranked 39th in the world in education and we spend more money than any country so if we didn’t learn by now throwing money at the problem isn’t going to help maybe our politicians are ranked 39th in the world in education or maybe somebody just needs more money in the pocket

The Upper Class & their big corporations are NOT paying their fair share of taxes!

Every tax in this state is higher than most. Property,School, gas, cigarette …all are ridiculous. That is why I am in the process of selling my house and moving to Virginia or Florida

Answer one very simple question…..why has the year over year increase in education funding through property taxes yielded a decrease in educational outcomes as measured by readiness for further education?

Our taxes are now over $5,000 per year, it’s a major hardship!

I see people on here saying to vote one party or the other out. Both are an issue. Neither side really seems like they want to do anything to work on the problem. A lot of things need work to actually help the kids that need it. School district consolidation. Tenure. Taxes. Retirements (public ones in general). All sides need the gumption to do it.

Shouldn’t we raise taxes back to what they were when the American economy was flourishing & the US government was running a surplus (and paying off the national debt)? – isn’t that what we all want?