The Lithuanian youth project “Mission Siberia” was launched in 2006. Its main goal is to let young Lithuanians to visit places where Lithuanians were imprisoned into GULAG camps or were exiled during Stalin’s repressions.

After the annexation of the Baltic republics to the USSR in June 1940, NKVD officers started to arrest and send to the Gulag all people suspicious from the Communist point of view, including ordinary prosperous peasants. After the end of the WWII, many Lithuanians joined the formations of so called “forest brothers”, armed resistance to Soviet occupation. Soviet army and police forces had been violently crushing this resistance. The amount of Lithuanians that were sent to GULAG mostly in Siberia and also in Kazakhstan and other middle-Asian republics reached about 100 thousand.

The participants of the project annually sent expeditions of young people to different regions of Siberia, where, in agreement with local authorities and with their assistance, they took care of the graves of repressed compatriots buried there.

This year the Russian authorities did not allow the annual youth expedition “Mission-Siberia”, which was favorably supported by them during previous 16 years. They denied Russian entrance visas to the participants of the project.

The embassy of the Russian Federation stated that this was a compulsory response, since the Lithuanian side creates artificial obstacles that prevent Russians from looking after Soviet graves and monuments commemorating WWII. The position of Moscow on this issue was explained by the official representative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Maria Zakharova. She noted that in recent months, the Lithuanian authorities have been toughening their positions in matters of Russia’s memorial activities in Lithuania. In particular, all the repair and restoration works planned for the burial places of Soviet soldiers were actually frozen this year under the pretext of developing a new version of the “Rules for the Improvement of an Immovable Cultural Heritage of Significant for Foreign States” in the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania. According to Zakharova, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture of Lithuania did not follow the repeated appeals of the Russian embassy concerning this matter.

Russian position is that during WWII Russian army had freed Lithuania from the German Nazi slavery. Many Lithuanians though don’t see a difference between German and Russian occupation and happy to get rid of the numerous monuments of the communistic times.

Many residents of the Baltic States remember well how after the collapse of the Soviet Union, most Soviet-era symbols were destroyed or transferred. The most resonant was the dismantling of the monument to the Soldier-Liberator in Tallinn in 2007. Then the story of the transfer of the pedestal from the city center to the military cemetery ended in mass riots.

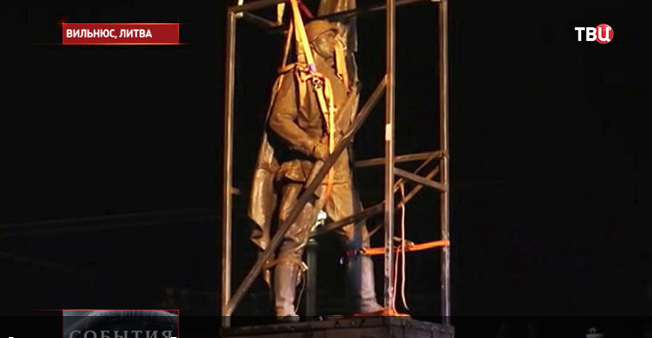

In the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, the sculptures of Soviet workers and soldiers, mounted on the main bridge of the city, were dismantled under the cover of the night. The formal pretext was that the statues, recognized as an object of cultural heritage, are dilapidated. But neither restoration nor return of the sculptures to the place were promised.

Vygaudas Usackas, the former head of the Lithuanian foreign policy department, ex-head of the European Union representation in Russia, wrote on his Facebook page: “The decision of the Russian government not to issue visas to the expedition members, in my opinion, only confirms their desire to erase the historical memory, not to allow young people to be interested in the stories of exiles, to break the backbone of our values.”

After the suspension of the “Mission Siberia” project, the organizers decided to send this year expedition not to Siberia, but to Kazakhstan, where about 50 thousand Lithuanians were also exiled. The ex-minister proposed to arrange the mass send-off of the project participants “so loudly that the Kremlin chokes.”

When the project “Mission Siberia” was just beginning, the adult generation of Lithuania was not sure that the young people would show interest in it. However, it was mistaken. This year there were more than 900 people, wishing to go just to Kazakhstan.

25 people were selected. The youngest participant of the expedition was 17 years old, the oldest one was 34.

There were no legal problems, since citizens of Lithuania can stay in Kazakhstan for 30 days without a visa.

For 11 days the team visited and fixed the graves of Lithuanians in 16 cemeteries in the vicinity of Karaganda, Zhezkazgan and Balkhash.

They found the most of the old cemeteries of the victims of repressions in the terrible conditions.

The members of the team recognized the graves of Lithuanians by the catholic crosses. They took care of the graves.

In addition, the expedition members met with ethnic Lithuanians still living in Kazakhstan, who told them their stories.

In Zhezkazgan team members met Vlad Rachkaytis, who was born in Kazakhstan to a family of political prisoners, who’ve met in the camp. He visited Lithuania only once. Despite this, he has been fluent in Lithuanian since childhood, although some phrases were already incomprehensible to him. When the visitors tried to speak with him in Russian, he was dissatisfied. He said that he wanted to speak with the participants of the mission in the “right” language.