Senate invokes constitutional provision against AG Kathleen Kane tied to era of eugenics, forced sterilizations, and the Holocaust

The Pennsylvania Senate, carelessly hoping to remove state Attorney General Kathleen Kane from office, has unwittingly invoked an obscure and long-forgotten clause in the state constitution that’s rooted in some of the darkest days in the commonwealth’s history.

The constitutional provisions, called “Direct Address” or “Direct Removal,” were added to the state constitution in 1874 to remove judges and other office holders.

The removal provisions are firmly tied to that historical period’s growing infatuation with identifying “mental defectives,” eugenics, forced sterilizations, and what eventually would lead to the Holocaust of World War II.

These forgotten provisions, remaining today like a shrunken appendix in Article VI Section 7 of the Pennsylvania constitution, were used only twice before in the state’s history, with varying and controversial results: in 1885 and 1891.

Century-old legislative records make clear that the provisions were meant to identify and remove judges and state office holders with mental or physical infirmities, and occasions not rising to impeachable offenses.

For example, in the 1885 case, which involved the removal from the bench of Pittsburgh Judge John Kirkpatrick, who evidently suffered a stroke, the legislature was told:

“There can be no doubt, but that the provisions of the Constitution for the removal of judges, on address of two thirds of both House of the Legislature, was intended to apply to cases where a judge had become incapable of discharging the duties of his office, from either bodily or mental infirmity…. So, if the mind and memory of a judge should become imbecile from old age or other cause (although not amounting to lunacy) and that should be satisfactorily proved, it would be the imperative duty of the Legislature to ask his removal.”

Problem was, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, medical science had yet to understand the causes or treatments of brain disorders, mental illness, or hereditary diseases.

The start of the Neo- Darwinian era in Pennsylvania

To understand the purpose and intent of these 1874 constitutional provisions, today’s Pennsylvanians must bear in mind the times and motivations in which they were added to the constitution.

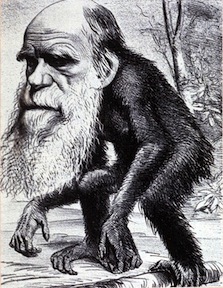

In 1874, in the Victorian era, the public was grappling with the implications of what was by far the greatest scientific insight of the age: the publication, fifteen years earlier, of Charles Darwin’s book On the Origin of Species, and his follow-up 1871 book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex.

Darwin’s two books, it’s fair to say, upended not only science, but also medicine, religion, society, and how people thought of themselves, and their origins, and the order of things.

Darwin’s work was every bit as disruptive in the nineteenth century as Einstein’s work would be in the twentieth. Perhaps even more so.

By the 1870s, young, forward thinking members of society, and Pennsylvania lawmakers, would find themselves grappling with the implications of Darwinian evolution.

Even so, no one, including Darwin himself, much understood the genetic or cellular mechanisms at work behind evolution and natural selection.

It would be another quarter century before Friar Gregor Mendel’s lost and ignored work on the science of genetics would be rediscovered, around 1900; and it wouldn’t be until much later, in the 1950s, that James Watson, Francis Frick and Rosalind Franklin would identify the structure of DNA in the double helix.

Until then, in the 1860s onward, a growing movement, led by Darwin’s half-cousin, statistician Francis Galton, would put forward the pseudo-scientific theory of eugenics to explain all sorts of societal and personal ills, and supposed solutions.

Galton wrote that just as physical traits were inherited, so were mental abilities. He argued that heredity must henceforth be guided by conscious decisions, so that the “less fit” not overrun the “more fit.”

“In Galton’s view, social institutions such as welfare and insane asylums were allowing ‘inferior’ humans to survive and reproduce at levels faster than the more ‘superior’ humans in respectable society, and if corrections were not soon taken, society would be awash with ‘inferiors,'” Wikipedia tells us.

It’s hard to overstate the impact all this had on Pennsylvania. In Pennsylvania, the eugenics movement grew like wildfire in the last decades of the 19th century.

Eugenicists, imagining that human problems could be viewed as problems of selection and breeding, proposed all sorts of outlandish and cruel solutions for supposed societal ills.

To address these problems, eugenicists in Pennsylvania, a hotbed of the pseudo-science, would come to advocate the forced sterilizations of prostitutes, those with mental conditions, prisoners and others.

The belief was that if society could identify “defects” like feeble-mindedness, imbecility, idiocy, lunacy, or loose sexual morals, society could, and should, take action and intervene.

Society could benefit by sterilizing or otherwise neutralizing the carriers of the problem, a concerned public was told.

All this sounded reasonable, scientific, and even forward-thinking in 1872 and ’73, when the attendees of Pennsylvania’s constitutional convention voted to include provisions for removing judges and office holders for reasons of “incompetency” and other loosely defined mental and physical infirmities.

At the time, these ideas were in the air and the Zeitgesit and held increasing sway in Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. This was simply the thinking of the day.

Eugenics code words, alienists, and the law

The Pennsylvania press at the time was literally awash in this dangerous eugenics nonsense, which often played in to, and gave validation to, the worst sort of stereotypes and political pressures.

For example, an article appearing on the top of page one in the June 10, 1885 Philadelphia Inquirer, only a few months after Judge Kirkpatrick’s removal from the bench, titled “Pauperism and Crime,” addresses the “evil” of poor immigrants.

“From the census of 1880 it was found that the proportion of the insane in the United States was one native born to every 662 native born citizens, and one … to every 254 citizens of foreign birth,” the Inquirer reports.

The implications were clear: foreigners bred insanity; and insanity, whatever that was, was two or three times more prevalent in foreigners than in native-born Americans. Stop the presses!

The Inquirer article is steeped in what can only be called eugenicist sentiment and code words. These sentiments and code words attempted to address and change laws.

On the surface, the problem, the Inquirer relates in its 1885 article on insanity and immigrants, involved federal immigration legislation that must be changed.

“The (1882 immigration) act was defective,” the Inquirer relates, “first, in that its execution depended entirely upon local officials influenced by political and local considerations; second, that examinations (of immigrants) were generally hurried and superficial,” and so could not effectively weed out the insane from entering our borders.

Beneath the surface, we understand today, there were deeper problems with this argument.

For one example, what was the clinical definition of “insanity?”

Literally, for most of the 1800s, there was none.

Emil Kraepelin, a founder of modern psychiatry, wouldn’t publish the first edition of his book Compendium of Psychiatry until 1883; he’d argue in Compendium that psychiatry was a branch of medical science, governed by observation and experimentation, like other sciences. He’d go on to classify disorders such as manic depression, and what would come to be known as schizophrenia. What made mental disorders recognizable, he argued, were not particular symptoms, which often could be shared by various disorders, but by a pattern of symptoms and how they evolve over time. Kraepelin referred to his classification of disorders as “clinical,” as opposed to what he called traditional “symptomatic” classifications. Before Kraepelin, there was no clinical psychiatry, or clinical definitions of disorders as we know them today.

Likewise, Kraepelin’s contemporary, Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, wouldn’t begin his study of “nervous disorders” until the mid-1880s.

The word psychiatrie, though coined in 1808 by German physician Johann Christian Reil from the ancient Greek, meaning “medical treatment of the soul,” wasn’t widely used in the nineteenth century.

Those who worked with the “insane” in this period weren’t called psychiatrists.

They were called alienists, because they dealt with those whose mental problems made them alien to polite society, and outsiders.

These alienists, who had little or no scientific knowledge of mental conditions, would preside at the first hearing under the state’s 1874 constitution to remove from office Judge john Kirkpatrick in Pittsburgh.

Most shocking of all, today in the twenty-first century, the Pennsylvania Senate proposes to apply these nineteenth century alienist and eugenicists’ ideas to Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen Kane.

Piggybacking on Progressivism

In his book, Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court and Buck v. Bell (Johns Hopkins, 2008) historian and attorney Paul Lombardo explains how the leaders behind the Eugenics Movement in the late 19th century cleverly latched on to other social movements of the day, like the anti-prostitution Purity Movement, the Hygiene Movement, the Temperance Movement, and, perhaps most importantly, the potent Progressive Movement, led by a new generation of American politicians, like Wisconsin’s Robert La Follette, and Pennsylvania’s own Democratic Gov. Robert Pattison.

“The Purity Crusade of the nineteenth century fed into the social hygiene movement of the twentieth,” Lombardo writes.

“A eugenic program could address goals of both the Purity Crusade and the social hygiene movement,” Lombardo explains. “While not discarding the rhetoric of sexual moralism they adopted from purity crusaders, many eugenicists began to repeat arguments from social hygienists that emphasized scientifically-based expertise as a pragmatic foundation for legal reform. This shift was entirely consistent with the even larger social movement that was a key underpinning of eugenic activities: Progressivism.

“Progressivism had many faces. Not so much a unified movement as a set of ideas pointing the way to reform, it arose in the last year’s in the nineteenth century and for nearly thirty years had an impact on U.S. political and social institutions. One trend that emerged under the banner of Progressivism was the desire to apply principles of efficiency to the management of government and to delegate the control of social welfare programs to a professionally trained class of experts.”

Eugenicists, with their goal of identifying mental or physical “defectives,” offered Progressives a course of action: removing “undesirables” and their traits from society and, eventually, forced castration and sterilization.

These actions would not only cleanse society, eugenicists promised. They would ease the burden on taxpayers who would no longer have to pay for the care and lodging of these “defectives” and their progeny in mental asylums, jail cells or, in some cases, public offices.

Lunacy laws, and removing state officials with mental defects from office

In cases of “mentally infirm” judges and other office holders, society wouldn’t be burdened, or their government offices slowed, if they were removed. Or so Pennsylvania lawmakers hoped in the 1870s. Hence, they wrote the constitutional provisions with which Attorney General Kathleen Kane today is threatened.

With all this in mind, Pennsylvania’s “Direct Address” removal provisions of 1874, and their legal terminology, become understandable.

I spoke by telephone with author Paul Lombardo, a professor of law at Georgia State University.

There were three categories of laws in the nineteenth century related to all this, Prof. Lombardo tells me, which can generally be defined as “commitment laws.”

The first were “guardianship” laws, dating to Colonial times, which primarily involved property rights. Guardianship laws “took away your personal responsibilities and you became a non-person,” Lombardo tells me. This, of course, he adds, simply didn’t apply to large swatches of children, women or slaves in the nineteenth century, who had no property rights.

The second involved criminal laws, such as insanity laws, which removed one’s criminal responsibilities from the commission of a crime.

“The third, and this sounds like what you’re talking about now in Pennsylvania, were the Lunacy Laws,” Lombardo says. “They declare you unable to care for yourself and take away your rights. You lose your legal personhood.”

Take, for example, the paragraph mentioned above that was read to the legislature in 1885 in the removal of Pittsburgh’s Judge Kirkpatrick from the bench. Kirkpatrick evidently suffered a stroke, and lost his ability to speak and think clearly.

The sentence read to the legislature: “If the mind and memory of a judge should become imbecile from old age or other cause (although not amounting to lunacy) and that should be satisfactorily proved, it would be the imperative duty of the Legislature to ask his removal.”

The operative words here were “imbecile” and “lunacy.”

What’s the difference? we might ask today.

In the nineteenth century, lunacy was a general condition that imparted the legal definition of insanity, Lombardo explains.

Imbecility, or idiocy, on the other hand, to the eugenicist, were specific mental deficiencies that could be measured and ranked.

To the nineteenth century eugenicist’s way of thinking, one could be an idiot, or an imbecile, even a moron, but that didn’t necessarily make you a lunatic, or a victim of lunacy, or insanity.

‘Profound idiot’

A eugenicist, then, as we see in the 1885 case of the removal of Pittsburgh Judge Kirkpatrick, set out to identify, categorize and rank the supposed differences between an idiot, an imbecile, a moron, and the unfortunate “feebleminded.”

These days, of course, all this seems like splitting hairs, doesn’t it?

“The plight of the ‘feebleminded’ ranked alongside epilepsy as a topic of special interest to professionals working in America’s (nineteenth century) institutions,” Lombardo writes in Three Generations. “According to Massachusetts physician Walter Fernald, those defined as feeble minded endured all manner of ‘congenital defect,’ ranging from ‘the simply backward boy or girl but little below the normal standard of intelligence to the profound idiot, a helpless, speechless, disgusting burden, with every degree of deficiency between these extremes.’ Fernald noted the distinction between idiocy and imbecility (imbeciles had slightly higher intellectual capacity) and concluded the term feebleminded was ‘a less harsh expression, and satisfactorily covers the whole ground.’ Worries about heredity feeblemindedness fed into concerns about sexual misconduct.”

“The emergence of feeblemindedness as a topic of public concern signaled a changing role for physicians, educators, and social workers who had ministered to the ‘less fortunate class,'” Lombardo continues. “…Feeblemindedness also opened clear avenues of activity for a professional class of reformers that could guide government policy in a Progressive direction.”

To identify the feeble minded, what commonly happened, Lombardo tells me, is that a set of doctors or other alienists from a local asylum would be appointed to examine a person to supposedly measure and categorize his or her supposed mental deficiencies, defects, or illnesses.

Often these professional alienists, in the nineteenth century, had little more practical experience or scientific knowledge than a horse doctor, and often much less.

PA’s direct removal provisions, Judge Kirkpatrick, and feeblemindedness

All this becomes necessary to our understanding of the 1874 Direct Address provisions that today’s legislators want to apply to Attorney General Kathleen Kane.

Sure enough, in the 1885 Pennsylvania legislative record of the “Investigation into the Condition of the Hon. Judge John M. Kirkpatrick, with a view to his removal,” as the report favoring the judge’s direct removal was called, members of the state Senate and House committee and their lawyers investigating Judge Kirkpatrick requested that three doctors from Pittsburgh’s Dixmont State Hospital for the Insane examine the sick judge, who was incapacitated, after all, not by insanity, but a stroke.

“We are not here for the purpose of prosecuting a case against Judge Kirkpatrick or anyone else,” attorney C.F. McKenna tells the committee, “but for the purpose of securing, as far as possible, a fair investigation of his physical and mental condition. And, with that purpose in view, (we) will call as witnesses three medical gentlemen of character and repute in their profession. We will ask this court this morning to designate these three gentlemen: Dr. Hutchinson, who has been connected with Dixmont for seven or eight years, and has made a special study of the treatment of the insane; Dr. C. C. Wylie, who, for a long period, was the acting superintendent of Dixmont Insane Hospital; and Dr. Samuel Ayres, a physician of this city who has served some years in the hospitals for the insane and devoted much study to their treatment, be designated by this committee as a committee of physicians to visit Judge Kirkpatrick at his home and make report in connection with their and other expert testimony to be given here this afternoon.”

This was a classic move from the eugenicist’s playbook: appoint a team of “professional experts” to examine one with a “defect.”

It would turn out that only one of these doctors from Dixmont, H. A. Hutchinson, a relatively young alienist, would be allowed to examine Judge Kirkpatrick.

“I think the judge is suffering from peretic dementia — loss of mind,” Dr. Hutchinson told the legislative committee. “He seems to be suffering from that; he seems to have lost his mind.”

But Dr. Hutchinson, not surprisingly, was incorrect.

Today, peretic dementia, also known as general paralysis of the insane, or GPI, is associated with the late-stage syphilis, and not a stroke. But Dr. Hutchinson couldn’t have known that in 1885.

“GPI was originally considered to be a type of madness due to a dissolute character, when it was first identified in the eighteenth century, until the cause-effect connection with syphilis was discovered in the late 1880s,” Wikipedia tells us. That would be a few years after Judge Kirkpatrick’s legislative examination. “Subsequently, the discovery of penicillin and its use in the treatment of syphilis rendered paresis both curable and even avoidable.”

Dr. Hutchinson explained that he had arrived at his diagnosis by taking Judge Kirkpatrick’s pulse, examining his skin, and speaking with the judge for fifteen minutes.

Couldn’t “mental trouble” like this be cured by proper diet and sleep? the doctor was asked.

Dr. Hutchinson said he had his doubts.

Perhaps Judge Kirkpatrick merely had “softening of the brain,” whatever that was, another suggested.

“I have cases under my care down at the hospital exactly like Judge Kirkpatrick’s,” the doctor advises.

The doctor uses the eugenicist’s hot-button code word, “feeble”:

Judge Kirkpatrick, “looked to me like a very broken-down man,” Dr. Hutchinson tells the committee. “He seemed feeble, and he looks weak. I asked him to walk for me, and we walked with a tottering movement, like a very old man — a very decrepit man — and he is not inclined to talk very much, and what he does say is not altogether what he would say were he in health, I think. He cannot express himself intelligently altogether.”

In fact, the word “feeble” appears repeatedly throughout Judge Kirkpatrick’s 1885 legislative Direct Address record.

“He was feeble,” Kirkpatrick’s supervisor, Pittsburgh President Judge Thomas Ewing, tells the legislature, and so on.

They were politely asking whether Judge Kirkpatrick had grown feeble minded.

Shortly after this legislative “investigation,” Judge Kirkpatrick would be removed from the bench by the legislature, with the approval of then-Gov. Robert Pattison.

Governors Pattison and Pennypacker

As I say, the Direct Address removal provisions in the Pennsylvania constitution would be attempted only twice to remove office holders: in Judge Kirkpatrick’s 1885 case; and six years later, in 1891, when Gov. Pattison failed to remove the state treasurer and auditor general from office.

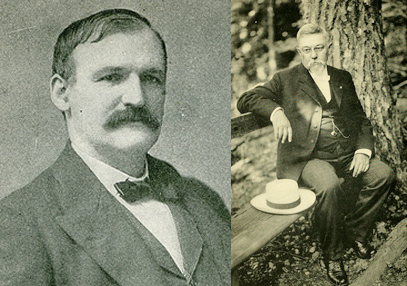

It should be noted that both of these attempts at Direct Address constitutional removal were undertaken with the blessing or involvement of Gov. Robert Pattison, of Philadelphia.

To understand both of these Direct Address actions then, we have to understand a thing or two about Gov. Pattison.

Robert Pattison was the only Democrat to hold the governor’s office in the 70 years between the Civil War and the Great Depression.

Pattison was first elected governor in 1882 at age 31, and remains the youngest man to serve as governor in Pennsylvania history, and one of the youngest in U.S. history. (Only a boy of ten at the start of the Civil War, Pattison was able to escape the common charge hurled at Democrats that they were Southern sympathizers during the war.)

Gov. Pattison in many ways was Pennsylvania’s Teddy Roosevelt. Young, brash, hard charging, critical of the Trusts and machine politicians, and forward looking, Gov. Pattison embraced the Direct Address provisions in the state constitution of 1874 to identify, categorize, and remove mentally and physically infirm officials from office.

Gov. Pattison successfully oversaw Judge Kirkpatrick’s Direct Address removal in 1885, and thereafter named Kirkpatrick’s replacement to the Pittsburgh bench.

Robert Pattison went on to serve two non-consecutive terms as governor, winning reelection in 1890.

In 1891, at the start of his second term, Gov. Pattison attempted to again use the Direct Address provisions to remove two political enemies, the Republican treasurer and the auditor general, for alleged financial chicanery.

But this time the Republican-dominated legislature refused to go along.

The Senate acquitted the treasurer and the auditor general; Gov. Pattison was told he had no jurisdiction to remove office holders using a constitutional provision meant for the removal of the mentally or physically infirm.

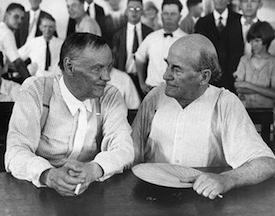

Pattison would leave the governor’s office in 1895. Still relatively young, he would be encouraged to run for higher offices. He ran for president in 1896, but lost the Democratic nomination to William Jennings Bryan. (We should probably remember that Bryan went on to serve as counsel in the 1925 Scopes monkey trial, “the capstone of his career,” in which he sought to prevent the teaching of evolution.)

Clarence Darrow, a famous Chicago lawyer, and William Jennings Bryan, defender of Fundamentalism, have a friendly chat in a courtroom during the Scopes evolution trial. Darrow defended John T. Scopes, a biology teacher, who decided to test the new Tennessee law banning the teaching of evolution. Bryan took the stand for the prosecution as a bible expert. The trial in 1925 ended in conviction of Scopes. ca. 1925 Dayton, Tennessee, USA

In 1902, Pattison sought this third non-consecutive term as governor of Pennsylvania.

This time Samuel Pennypacker, a Republican judge and historian, soundly defeated him. Pennypacker was an affable man with a rounded temperament and circumspect nature, and a great sense of humor.

Pattison would die in 1904, from stress of his last campaign for governor, The New York Times would report.

But that’s not the end of the story.

Eugenics reaches high mark in Pennsylvania and elsewhere

While Gov. Robert Pattison’s career rose and fell, the eugenics movement continued to grow in Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.

Pennsylvania hosted “the first known sterilization (castration) in a public institution in 1889 or 1892,” reports the University of Vermont.

In all, at least 270 sterilizations would be performed in Pennsylvania between 1889 or 1892 and 1931, all without the benefit of law, reports the university.

“There was only one location where sterilizations were performed: the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children at Elwyn was the location of all 270 sterilizations,” the University of Vermont notes. “It is the second oldest care facility for the mentally disabled in the United States, founded in 1852 as the Pennsylvania Training School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Children. It was actually opened in Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1854 and moved to Elwyn in 1857. The building complex is currently in use as a service provider for the mentally retarded. The website for the institute, which is now known simply as Elwyn, no longer makes any mention of sterilization or the eugenics movement.”

Today’s Elwyn institution then has this in common with today’s Pennsylvania Senate: neither makes mention of their long and dark association with eugenics, and forced sterilization.

In the 1890, a Kansas physician castrated 58 children in his Winfield, Kansas, Institution for Feeble minded Children.

Shortly thereafter, a physician “asexualized” 26 patients at an epilepsy asylum in Massachusetts.

In Pennsylvania in 1892, Dr. Isaac Kerlin “operated not only to curb an ‘epileptic tendency’ in the patient but also to remove her ‘inordinate desires which (were) … an offense to the community,” Lombardo writes. “He challenged the states to take the lead in legalizing surgery ‘for the relief and cure of radical depravity.”

All this became a slippery and dangerous slope, embarked upon in the 1860s and 70s with the best of intentions. By imaging we can do God’s work, we often do the devil’s work instead.

Within a decade, in the 1910s, eugenicists would suggest sterilization, and worse, as “a solution to the Negro problem.”

Not long thereafter, Adolf Hitler and his Third Reich would incorporate these very eugenic policies, once endorsed wholeheartedly by Pennsylvania lawmakers, into his Final Solution for Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, and others who were deemed defective, undesirable, or degenerate. Tens of millions of people would die.

Back in Pennsylvania, where all this tragedy had taken legal root in the 1874 constitution, and other laws, eugenicists continued to hold great sway in to the early 1900s.

Teams of men were kept gainfully employed in the field by the eugenicists, traveling this and other states to find and categorize entire towns and hamlets inhabited by generations of idiots, imbeciles, drunkards and sex fiends.

I can see from this that I was born one hundred years too late, as in Pennsylvania this would have been a challenging, lucrative, and never-ending job.

“Pennsylvania considered a ‘Bill for the Prevention of Idiocy’ in 1901 that specifically focused on ‘mental defectives’ in institutions,” Prof. Lombardo recounts in his book. “The bill declared that ‘heredity plays a most important part in the transmission of idiocy and imbecility,’ and it authorized surgeons to ‘perform such operation for the prevention of procreation as shall be decided safest and most effective.’ The bill passed both chambers of the Assembly but was returned by Governor William Stone ‘for some trifling technicality.’ It failed to become law.

“The legislation offered in 1901 was reintroduced in 1905 and endorsed by both sides of the Pennsylvania legislature ‘without meeting any very determined opposition,'” Lombardo notes.

Gov. Samuel Pennypacker vetoed the state’s Idiocy Prevention Bill in 1906, though the Pennsylvania legislation went on to become a model for other state laws.

Vetoing the Prevention of Idiocy Bill, Gov. Pennypacker wrote:

“It is plain that the safest and most effective method of preventing procreation would be to cut the heads off the inmates, and such authority is given by the bill to this staff of scientific experts… Scientists like all men whose experiences have been limited to one pursuit … sometimes need to be restrained. Men of high scientific attainments are prone … to lose sight of broad principles outside of their domain… To permit such an operation would be to inflict cruelty upon a helpless class … which the state has undertaken to protect.”

“Pennypacker should probably be celebrated for this early criticism of faulty eugenics legislation,” Prof. Lombardo writes, “but he is probably remembered more for a related anecdote that demonstrates his adeptness at handling the press.

“At the end of his term, he attended a press ‘roast’ put on by the reporters who had chronicled his administration. His introduction was met with the barrage of catcalls and boos common to such occasions, to which Pennypacker is reported to have calmly replied:

“‘Gentlemen, gentlemen! You forget you owe me a vote of thanks. Didn’t I veto the bill for the castration of idiots?””

From this we learn, on good authority, that the imbeciles work in the legislature, while the idiots tramp the fields of the Lord in the press room.