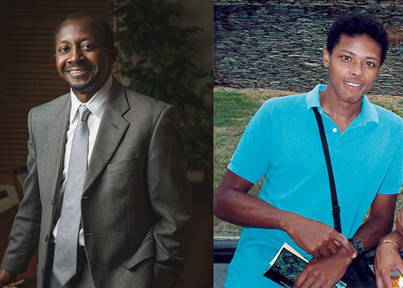

Prominent Baltimore defense attorney Kenneth Ravenell (left), once a self-described ‘good friend’ and ‘mentor’ of murdered federal prosecutor Jonathan Luna (right)

Prominent Baltimore defense attorney Kenneth Ravenell, once a self-described ‘good friend’ and ‘mentor’ of murdered federal prosecutor Jonathan Luna, has been indicted for alleged collusion with a drug kingpin. Ravenell served as defense counsel on two of prosecutor Luna’s most mysterious cases, including Luna’s last case.

By Bill Keisling, yardbirdbooks.com/

Stunning developments unfolding in Maryland law enforcement circles not only involve people once close to slain federal prosecutor Jonathan Luna. They resemble plot twists from the Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul TV shows.

Assistant United States Attorney Luna was found dead in a stream near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in December, 2003. His death was ruled a homicide by the Lancaster County coroner. The perplexing and infamous murder remains unsolved.

Sixteen years later, a defense attorney who worked on two of Luna’s most dramatic and controversial cases has been indicted by the U.S. Attorney’s office in Baltimore for allegedly working for years on the wrong side of the law with a drug kingpin.

A federal grand jury indicted Kenneth Ravenell in late September 2019 for diverse offenses related to the alleged use of his law offices in collusion with a Jamaican drug boss. Charges against attorney Ravenell include alleged racketeering conspiracies, money laundering and drug trafficking. (Read the indictment here.)

Ravenell, for decades a prominent pillar of the Baltimore legal establishment, has pleaded not guilty and denies any and all wrongdoing.

Among other alleged infractions, federal prosecutors accuse Ravenell of schooling drug clients on how to use burner phones, and other methods to avoid law enforcement detection.

“Ravenell instructed members of the conspiracy to remove batteries from their cellular devices and leave their phones outside meetings held to discuss illegal activities in order to prevent such meetings, including meetings held within the offices of The Law Firm, from being recorded by law enforcement,” alleges the indictment.

“Ravenell instructed members of the conspiracy to utilize certain drug couriers, to utilize specific modes of transportation, and to transport shipments of drugs and money at particular times of day, all for the purpose of evading law enforcement,” the indictment reads. And, “Ravenell instructed co-conspirators to use payphones and in-person meetings when discussing drug trafficking in order to minimize the risk of being intercepted by law enforcement.”

The indictment further alleges that “Ravenell obtained access to incarcerated co-conspirators, whom he did not represent, so that Ravenell, S.G., and others could attempt to improperly influence their testimony, attempt to cause them to execute false affidavits and witness statements which Ravenell and S.G. knew to be false, and attempt to cause witnesses to withhold testimony from official proceedings, namely, a federal criminal case against R.B. in the District of Maryland.”

If all this seems strangely reminiscent of something, perhaps you just watched a recent episode of Better Call Saul, webcast in March 2020, in which the protagonist/antagonist lawyer, Jimmy “Saul Goodman” McGill, is “retained” by a South American drug kingpin to visit a defendant in prison to arrange false testimony offered to federal DEA agents.

Ravenell’s attorney, Lucius Outlaw III, a Howard University law professor, issued a statement to the Baltimore Sun: “Ken Ravenell has dedicated the past 30-plus years and counting to representing people in the toughest fights of their lives. He is held in high esteem by the criminal defense bar of Maryland, the state and federal judges of Maryland and many other jurisdictions, his clients, and the wider Baltimore community. He has the support of his family, especially his wife Kay and his five children. While he regrets that this fight has been unfairly brought to him, he will not run away from it, and he looks forward to proving his innocence and defeating the government’s five year and running effort to tarnish his name.”

Ravenell’s trial was scheduled to begin this April 13, but may now be postponed “until after … additional charges are returned,” federal prosecutors in late February 2020 told the court.

Prosecutors asked the court to seal the motion from the public, as the information it contains, they wrote, may “thwart an ongoing criminal investigation by leading individuals to engage in additional obstructive conduct, destroy evidence, and flee from prosecution.”

Ravenell and Luna’s last case

At the time of prosecutor Jonathan Luna’s death, Ravenell was one of two attorneys, with fellow Baltimore lawyer Arcangelo Tuminelli, defending heroin dealers Deon Smith and Walter Poindexter, respectively. The Smith-Poindexter case, tried in December 2003, turned out to be Luna’s last prosecution.

Luna disappeared from his office in the federal courthouse in Baltimore shortly before midnight on December 3, 2003, as the case drew to an unexpected and strange conclusion.

In the final hours and days of his life, court records show, Luna struggled with the fallout of the heroin distribution case. Earlier on the day that Luna disappeared, federal Judge William Quarles ordered an investigation into the handling of an FBI informant who was Luna’s main prosecution witness.

During trial it developed that the agents in the FBI’s Baltimore field office had had allowed the drug informant to run wild on the streets of Baltimore. The court heard evidence that the FBI’s confidential informant (CI) continued to deal heroin while under FBI supervision, and received undisclosed perks while working for the U.S. Justice Department.

Attorneys Ravenell and Tuminelli charged that Luna had improperly kept these problems from defendants Smith and Poindexter, violating their Brady rights, and Judge Quarles agreed. Quarles ordered an investigation of the FBI’s “kid-glove treatment” of the informant. The inquiry was to begin in court the next day — what turned out to be the day Luna was found dead seventy miles away in a stream in rural Pennsylvania.

These revelations about a FBI informant running wild in the streets of Baltimore came at a very politically sensitive time. Only a few months earlier another heroin dealer pleaded guilty to burning down a house owned by the Dawson family, burning the family to death so he could deal heroin on their street corner, all the while he was out of jail on unsupervised probation. The city was up in arms.

The FBI’s informant in the Smith-Poindexter case was caught with heroin on the same day the Dawsons’ house burned down in Baltimore. It wouldn’t do to have Baltimoreans know that another heroin dealer ran wild in the city while supposedly under FBI supervision.

To stave off an investigation and to shut down the troubled Smith-Poindexter case, Luna’s supervisors in the Baltimore U.S. Attorney’s office, late in the day of December 3, instructed Luna to offer the defendants a plea deal. Make it all go away.

But there was a problem. In earlier court documents Luna had alleged that one of the defendants, Tumineli’s client, had engaged in a drug-related murder connected to the case. If true, the murder would have rendered the defendant ineligible for a plea deal. On the evening of his death, Luna was overheard arguing with attorneys Ravenell and Tuminelli.

As they exited the courtroom on the last day of Luna’s life, court reporter Ned Richardson recalled that Luna was engaged in a heated argument with attorneys Ravenell and Tuminelli about the terms of the plea deal.

The three lawyers walked a brief distance down the hall and continued their heated argument outside the office of court reporter Richardson, who himself has just returned with the court record, Richardson recalled.

“My office is near the courtroom,” Richardson says. “I was in my office on my computer working on the trial transcripts. I heard Jonathan, Ravenell and Tuminelli outside in the hall arguing about conditions of the plea agreement.” Their disagreement was heated, loud and disruptive, Richardson vividly remembers.

“They were making so much commotion I was afraid I’d make some mistake with my computer and my notes,” Richardson says. He says he stuck his head out his office door and told them, “Take it somewhere else, guys.”

The proposed plea deal would remain unfinished on Luna’s computer in his office the next morning, while Luna lay dead in a stream scores of miles away in Pennsylvania.

S’all good, man!

Court transcripts relate that in the courtroom on the morning of Luna’s death, while Luna’s whereabouts still remained unknown, attorney Tuminelli told Judge Quarles, “I believe that we did work out the terms of the plea agreement. I spoke with Mr. Luna at 9:00 pm last night.”

“Uh huh,” Judge Quarles says.

“He (Luna) called me at home and said, you know, ‘I just want to make sure that we got all the details,’ he went over the details and I said that is correct. He said, ‘I left the office but I have to go back and complete the agreement.'”

“And he was supposed to fax the agreement to me sometime last night,” Tuminelli says.

“Have you seen the paper yet?” Quarles asks.

“No, because he was supposed to fax it during the evening. It was not faxed,” Tuminelli says.

With the young prosecutor nowhere in sight, Luna’s erstwhile supervisor, Assistant U.S. Attorney (AUSA) James Warwick, chief of the office’s criminal division, arrived in the courtroom and asked Judge Quarles for a fifteen minute recess so that Warwick could go to Luna’s office to find the unfinished plea deal that Luna walked away from a few hours before his death. Warwick ended up signing the rushed plea deal for Luna. (Click here to read a detailed account of the remarkable courtroom events to complete the plea deal on the morning of Luna’s death.)

“May I ask for the court’s indulgence in giving me fifteen minutes to finalize any changes with Mr. Ravenell and to find out where the heck that other document is?” Warwick asks Judge Quarles. Warwick proceeds to Luna’s office, finds one completed plea deal on Luna’s laptop, along with the uncompleted plea deal for the defendant involved in the alleged drug-related murder. He cuts and pastes between the two documents in a slapdash fashion to complete the deal. Warwick then signs Luna’s name to the plea agreement, and initials it.

“Mr. Tuminelli spoke with (Luna) last night and he was supposed to fax down the plea agreement,” FBI Special Agent Steve Skinner, handler of the errant informant, told the judge. “It was still in his computer up in his office, and we have paged him, and his cell phone is on his desk, his glasses are in his office. We are probably going to go over to the parking garage where he– where we park and just look for his car.” (Emphasis added.)

Court stenographer Ned Richardson here takes careful dictation. Skinner starts to say this is where Luna parks, but then stops to say it’s where “we” park. From this we glean not only that the agents park where Luna parks, but also that they know the car Luna is driving. They were going to “look for his car.”

Ravenell, for his part, in the courtroom on the morning of Luna’s death, says to Judge Quarles, “Your honor, I was going to ask the court just to take a recess until we find out what’s going on. You know, as much as we’re concerned obviously about the jury, and about the defendants, I mean all of us are personally concerned about Mr. Luna. I think that we need to try to let the (FBI) agents focus on trying to find him.”

Left behind: cell phone, eyeglasses, and laptop

A short while later the head prosecutors in Luna’s U.S. attorney’s office were informed that Luna was found dead in an icy stream in rural Pennsylvania. He’d been stabbed dozens of times, his throat slit, nearly ear to ear. His Justice Department ID badge still hung around his neck. As FBI Special Agent Skinner told the judge, Luna’s cellphone, eyeglasses, and laptop computer, the latter containing the unfinished plea deal, remained behind in his office. He also left behind a widow, and two young boys.

We know Luna had a portable laptop on his desk, because during the Smith-Poindexter trial Luna tells Judge Quarles about a piece of evidence on it. “It’s a videotape,” the court transcript reads. “We have reduced all of the videotapes to a computer file which is stored in the laptop at my desk.”

The things he left behind in his office are at once tantalizing clues, and perplexing riddles. Who gets up and goes for a drive leaving behind a cellphone, eyeglasses, and a laptop computer? Luna’s friends say he needed his eyeglasses to drive. Did he have a second pair? Did he carry a second cellphone? (One close friend tells me he never saw Luna with two phones.)

On the night he died Luna left his office at Baltimore’s Lombard Street federal courthouse shortly before midnight. The FBI timeline of events (see below) notes only that Luna left the courthouse parking garage, across Lombard Street from his office in the courthouse, at 11:38pm. His car’s E-Zpass was next tracked passing through the Fort McHenry tunnel toll plaza, northbound on Interstate 95, eleven minutes later at 11:49pm. Had Luna been heading home, he would’ve been heading south, not north. And the eleven or twelve minutes to pass these two waypoints doesn’t leave much wiggle room: it’s about the amount of time it takes at night to drive from the courthouse to the toll plaza. What’s going on here?

There would seem to be several possibilities, or combinations of possibilities. Either Luna left the courthouse alone, coolly, accidentally forgetting his personal items, or hurriedly, in hot blood; someone came into his office and Luna voluntarily, or under orders, left the courthouse and parking garage with this person(s); Luna was intercepted in or near the parking garage by his assailants, or at a traffic intersection not far away, before he reached I-95; or Luna drove off alone, heading north, intent on rendezvousing with someone.

Luna may have stepped outside the courthouse to make a phone call from a second (burner?) phone, or to meet with someone, and was intercepted there. Or he could have driven away from the parking garage and was intercepted by his killers at a red light on Lombard. The timeline’s tight, but not impossibly tight, for that scenario.

No video showing Luna leaving the courthouse has ever been released by authorities. The courthouse is, and was at the time, covered with video cameras, inside and out, in seemingly every hallway. U.S. Marshals’ Service security officers monitor the video on banks of screens at the front desk in the lobby of the courthouse, and any video is presumably recorded.

The Justice Department has never released a single frame of video of Luna leaving the courthouse. Does that mean for some reason the video doesn’t exist, or that it was destroyed? Some students of the case suggest that Luna was “marched out of the courthouse by someone with a badge and a gun,” and that explains the things he left behind. But that would mean the courthouse video cameras either were disabled, weren’t working, or the FBI knows who did this and his been lying about it for fifteen years. This seems to be the ultimate conspiracy theory, involving the FBI, the U.S. Marshall’s Service, the U.S. attorney’s office, and who knows who else. Perhaps not impossible, but unlikely. Perhaps the courthouse closed circuit television (CCTV) system simply was shut off so late at night, and there is no video. The Justice Department and the FBI owe the public an explanation on this important point.

It’s more reasonable, in my mind, to presume that Luna left his office in the courthouse alone, and there must be some other explanation for the things he left behind. But what’s the explanation?

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has Sherlock Holmes say. Still, Occam’s razor suggests that when there are multiple explanations for an event, the one that requires the smallest number of assumptions is usually correct.

Was Luna’s rendezvous with death a chance encounter? Or had someone tipped off Luna’s whereabouts and movements to his killers? Was Luna intercepted sometime after he left the parking garage across from the courthouse on Lombard St.? Where, why and how? remain tantalizing mysteries.

Ravenell and Luna both sign stipulation that missing $38,100 was returned to evidence locker

Following the announcement of Luna’s death, indicted defense attorney Ravenell described Luna as “a good friend.” Ravenell told the Associated Press, “I was kind of his mentor in many ways. He’d call me often and discuss things outside of what we did on cases.”

The December 2003 Smith-Poindexter case wasn’t the only extraordinary case shared by Luna and Ravenell.

Another strange incident in a criminal case involving Ravenell hung over Luna’s head at the time of his death. Defense attorney Ravenell represented bank robber Nacoe Brown in a September 2002 federal trial in which Luna was the prosecutor. At that trial, $38,100 dollars in evidence money vanished into thin air from the courtroom. Both Luna and Ravenell signed a court document stipulating that the exhibits, including the money, were returned at end of trial. (Click here to read a detailed account of the missing $38,100.)

At the time of his death, Luna was taking a lot of heat from his superiors in the prosecutor’s office about the missing money. They were demanding he take a lie detector test. He feared for his job, and had sought advice from a private defense attorney. Somebody leaked the story, and Luna had all but been openly accused of taking the missing money in a Baltimore Sun article.

After his murder, Luna’s wake was interrupted by a team of FBI agents who unsuccessfully searched for the missing evidence money while grieving friends and relatives looked on. The whereabouts of the missing $38,100 has never been established.

Warwick: ‘Do we have a deal or not?’

Ravenell found himself under investigation by the FBI and other authorities for years before his late-2019 indictment. His law offices were repeatedly searched by investigators, setting off ongoing appeals court challenges to the searches on concern of breach of attorney-client privileges.

Ravenell’s stunning prosecution shares another coincidence with Luna’s last hours and days on earth.

Ravenell’s indictment alleges that Ravenell was involved in drug-related activities with a client identified only as “R.B.” “R.B. operated a multi-state illegal drug trafficking organization and was an associate or client of Ravenell at all times relevant to this Indictment,” the document reads. “R.B. became a client of (Ravenell’s law firm) on or about February 21, 2011.”

The Baltimore press quickly deduced that “R.B.” referred to a Jamaican drug dealer named Richard Byrd. “The allegations center on the years of 2009 to 2014, during which (Ravenell) worked for the prestigious law firm of William H. ‘Billy’ Murphy Jr. and defended Jamaican national kingpin Richard Byrd,” the Baltimore Sun reported a few days after Ravenell’s indictment.

Byrd pleaded guilty to drug-related offenses in 2016, shortly before his trial was to begin. He was sentenced to 26 years in prison for conspiracy to distribute cocaine and marijuana, and money laundering.

The prosecutor of the 2016 Byrd case was AUSA James Warwick, Luna’s former boss who violated the crime scene of Luna’s office on the day of Luna’s death to cut the questionable plea deal for Smith and Poindexter.

The Baltimore Sun reported in 2016 that Warwick asked defendant Byrd at his trial, “Do we have a deal or not?”

– Bill Keisling

Jonathan Luna’s Midnight Ride timeline

Here’s the timeline of stops made by Jonathan Luna in the hours before his death, as released by the FBI:

Dec. 3, 2003:

• 11:38 pm – Luna’s vehicle departs the U.S. Courthouse in Baltimore

• 11:49 pm – Luna’s vehicle passes through Fort McHenry Tunnel Toll Plaza in Baltimore, northbound on Interstate 95

Dec. 4, 2003:

• 12:28 am – Luna’s vehicle continues northbound and passes through the Perryville Toll Plaza in Maryland

• 12:46 am – Luna’s vehicle passes through the Delaware Line Toll Plaza

• 12:57 am – Luna’s debit card is used at an ATM at JFK Plaza in Newark, Del.

• 2:37 am (approximate time) – Luna’s vehicle gets on the New Jersey turnpike at Exit 6A, from Route 130

• 2:47 am – Luna’s vehicle enters the Pennsylvania turnpike at Exit 359, the Delaware River Bridge

• 3:20 am – Luna’s debit card is used at a Sunoco gasoline station, King of Prussia, Pa., to purchase gas

• 4:04 am – Luna’s vehicle exits the Pennsylvania turnpike at Exit 286, the Reading/Lancaster interchange

• 5:30 am – Luna’s body is discovered off Dry Tavern Road in Denver, Pennsylvania

Related links:

Ravenell indictment (September 19, 2019)

DOJ press release: Baltimore defense attorney facing federal indictment (September 18, 2019)

Witness: Luna stabbed in back, his hands and scrotum slashed

Bank robber robbed in Baltimore federal courthouse

Missing evidence money documents

Embattled FBI agents disrupt mourners gathered at Jonathan Luna’s home